Universal Music Group — Music is Universal

There are few things surer than the predilection of humanity for music. It is the shorthand of emotion, as Tolstoy once quipped. All societies throughout history have developed their own musical language; whether it stemmed from the lyre (ancient Greece), the lute (medieval Europe) or the well-tempered clavier (an absolute game-changer that gave birth to the modern piano and in a way, all music that came after it). Warren Buffett’s case for investing in Gillette was famously simple: most men shave, and most men will continue to shave ‘til day dot. Our thesis on UMG is similarly simple: Music is Universal.

Universal Music Group (UMG) is one of the “big three” music publishing companies (the other two are Warner Music and Sony). Like its brethren it is the result of decades of industry consolidation and hence it is a diverse collection of assets which management has pieced together into a coherent whole (whilst UMG’s origins stretch back to Decca Records, in 1934, its various assets has, at points, been owned by Panasonic and prior to that Seagrams, the distiller). UMG now holds a 32.1% market share globally, which makes it the largest in the industry. It also is the only publisher to have consistently grown its revenues from 2018-2021, largely due to its embrace of streaming and modern mediums of music consumption (Spotify and the other streamers, TikTok, music licensing on memes and so on).

We like industries which have been subject to consolidation, especially ones that are progressing towards an oligopolistic structure. Industries at their birth are often dense with competition. In 1896, when the bicycle became popular there were 140 publicly listed companies engaged in the manufacture of bicycles; by 1901, 40 of those had gone bankrupt and over the next ten years another 60 had gone out of business. The invention of the bicycle was a significant advance in technology (in some ways, it was the most egalitarian advance in technology since the printing press – no fuel needed and relatively cheap and accessible). Yet a significant new technology is no guarantee of a successful business. The more businesses engaged in a new technology, the more competition, and the less chance the business will produce what we are all interested in at the end of the day – significant cash flows.

The catalyst for the recorded music industry were the twin inventions of the radio and recorded sound (first on wax cylinders which quickly evolved to vinyl discs). The two were bound together tightly; recorded sound allowed for the first time in history for music to exist outside of the present. Radio allowed for the effective “streaming” of it in a way which allowed almost unlimited distribution. The fortunes of the two industries were, for a time, linked at the hip. There were numerous recorded music companies and numerous radio companies. Both industries consolidated; for instance CBS transitioned from a radio station operator to a TV company, as did NBC. Decca (the historical precursor to UMG) merged with Universal-International and later MCA. Now the music industry has consolidated further resulting in the “Big 3” and the other side of the transaction – now streamers, not radio – are consolidating, too. There are therefore two catalysts that inform our view of UMG: the wider consolidation that has largely resulted in oligopolistic market share, and the virtuous nature of the other side of the transaction - streamers - and industry consolidation continuing amongst these players.

A virtuous cycle

There are two sides to a music transaction; the ownership of it and the distribution. The ownership of the song/track by the record company (often in tandem with the musician’s own company) is broken into two parts - the “master” rights and the “publishing” rights. The record owner of the rights receives royalties in three ways: mechanical royalties (.ie. the reproduction of the work; this is where revenue from streamers occurs), public performance royalties and synchronisation license fees (i.e. when a work is used in any derivative fashion; think of the sample in Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby” which is taken from Queen’s “Under Pressure” - every time “Ice Ice Baby” is played, the owner’s of “Under Pressure” get a royalty too).

Streamers, like Spotify, which investors in the Elevation Global Shares Fund own a share of, receive revenue from their subscribers; in turn Spotify pays a proportionate royalty to the rights owner; often this is UMG. This is counted as a ‘mechanical royalty’. Other popular apps - like TikTok - pay a performance royalty when users make content which uses a song.

We quite deliberately own both ends of the transaction. Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund own UMG via a direct holding, but also through our ownership of Tencent (the Chinese technology stalwart that owns 20% of UMG) and Prosus (a South African holding company which owns 28.9% of Tencent, and Vivendi, which spun-off UMG in 2021 and continues to hold a 10% stake). We also own Spotify (and we published research on it in April 2020 and an update in July 2020).

Why do we own both sides of the transaction?

The reason is quite simple. The two are correlated; the more people who stream music, the more royalties UMG will receive.

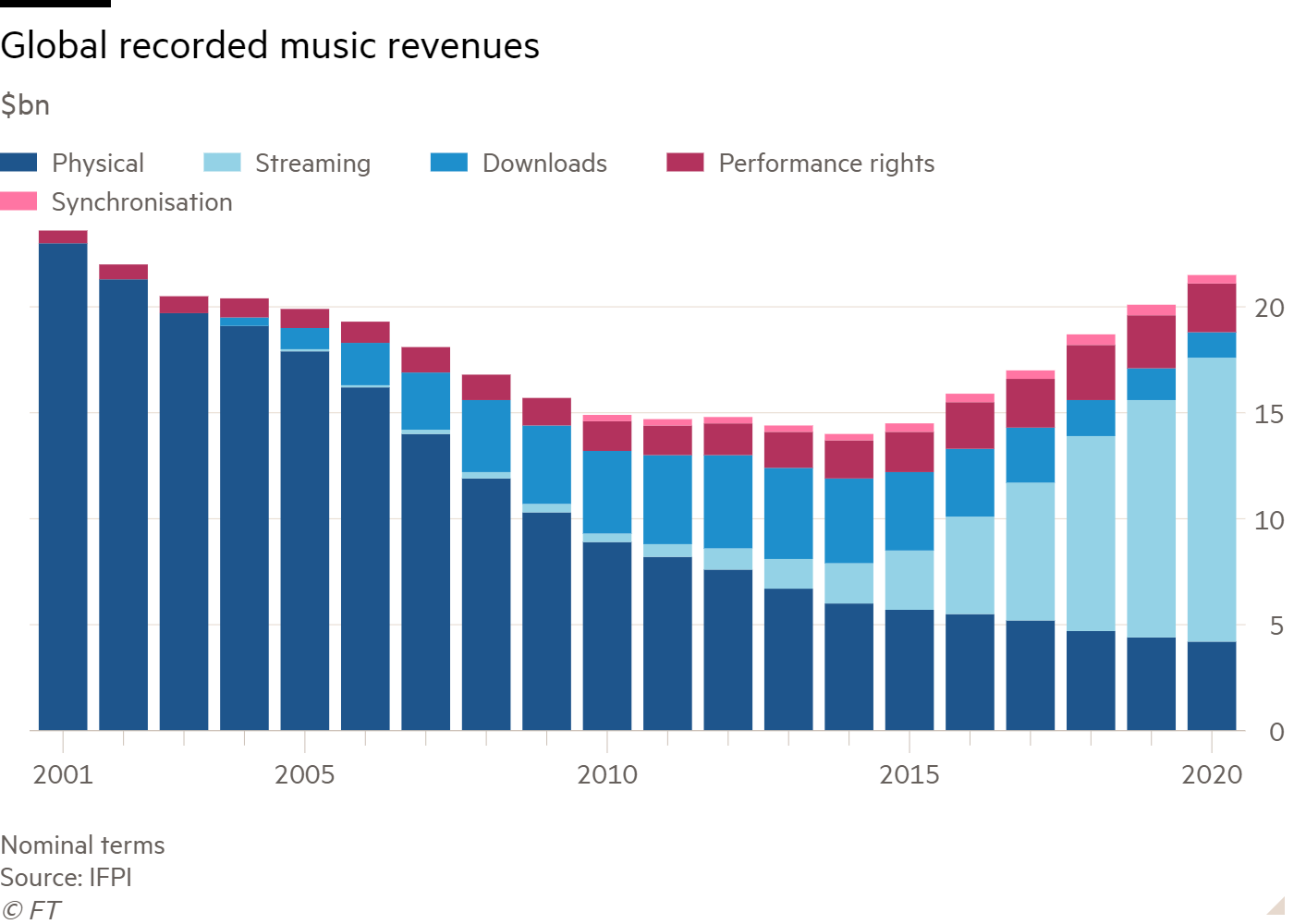

Source: Financial Times

The music industry has gone through two major disruptions in the last twenty years. The first is the “death” of the physical format - the CD - and the ascent of downloaded music. The second was the “death” of downloaded music and the ascent of streaming. Something happened between the 2000s and years following; total revenues declined, hitting their nadir in 2014. It’s important to understand what happened to understand what occurred next: in effect, the record companies didn’t know how to pivot towards a new digital era. Pirating of music was rife but also downloading music is a laborious process compared to a streamer, where millions of songs sit at your fingertips. The industry had continued to pour the bulk of its efforts towards the physical format (CD’s), which was a dying format – the iPod had seen to that. Secondly, the music industry couldn’t quite profit from downloads enough. The frequency wasn’t great enough.

Streaming changed this. Music industry revenues have now recovered to their early 2000s heyday directly proportional to the number of users on the various streaming platforms – Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, YouTube Music, Amazon Music, etc. The secret is the increase in frequency – whilst streams pay mere fractions of a cent per song play to the record company, the frequency is much greater. This bears many similarities to the co-dependent relationship of recorded music and radio which occurred at the advent of the medium. In other words, it’s full circle: streaming is radio, and the two are highly correlated.

Well positioned

We aim to not make hyperbolic statements and claim something is the “greatest” in its field. Leica is undoubtedly a great camera brand yet the best selling “camera” is the smartphone. As we have mentioned previously, the recorded music industry has a “Big 3” which all benefit from the same base advantages. UMG has the same advantages that both Sony Music and Warner Music have. However, UMG is slightly unique. The first is that it still retains a meaningful stake in Spotify (~3.4%). Sony Music has reduced its holding in Spotify to ~2.0% and Warner Music sold its stake entirely. UMG also owns ~1.0% of China’s most popular streaming service - Tencent Music. It is clearly in UMG’s best interest for streaming to succeed; as streaming’s fortune rises, so do those of UMG, and vice versa. It also means UMG has “skin in the game”; contrast this to that of the comparatively distanced approach record companies had to downloaded music in the first iteration of non-physical music.

The other quality that distinguishes UMG from its competitors is a technology-led commitment to the future. The company moved its headquarters from New York to LA, in a bid to be closer to the heart of the technology sector, as well as engaged proactively in agreements with next-generation services that use its content, like TikTok. It is easy for this to come across as corporate double-speak yet mediums like TikTok are more than hype; performance royalties have become a meaningful aspect of music industry royalties.

Finally, there is the most obvious aspect of size. UMG is the largest record company by far. UMG has used this advantage of scale to negotiate favorable agreements with partners such as Spotify, YouTube and TikTok. Their pricing power is obvious – platforms which do not have UMG’s content are missing out on perhaps a third of all recorded music. To once again quote Sumner Redstone: Content is King.