THE SUPERINVESTORS

OF GRAHAM-AND-DODDSVILLE

by Warren E. Buffett

“Superinvestor” Warren E. Buffett, who got an A+ from Ben Graham at Columbia in 1951, never stopped making the grade. He made his fortune using the principles of Graham & Dodd’s Security Analysis. Here, in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of that classic text, he tracks the records of investors who stick to the “value approach” and have gotten rich going by the book.

Is the Graham and Dodd "look for values with a significant margin of safety relative to prices" approach to security analysis out of date? Many of the professors who write textbooks today say yes. They argue that the stock market is efficient; that is, that stock prices reflect everything that is known about a company's prospects and about the state of the economy. There are no undervalued stocks, these theorists argue, because there are smart security analysts who utilize all available information to ensure unfailingly appropriate prices. Investors who seem to beat the market year after year are just lucky. "If prices fully reflect available information, this sort of investment adeptness is ruled out," writes one of today's textbook authors.

Well, maybe. But I want to present to you a group of investors who have, year in and year out, beaten the Standard & Poor's 500 stock index. The hypothesis that they do this by pure chance is at least worth examining. Crucial to this examination is the fact that these winners were all well known to me and pre-identified as superior investors, the most recent identification occurring over fifteen years ago. Absent this condition - that is, if I had just recently searched among thousands of records to select a few names for you this morning -- I would advise you to stop reading right here. I should add that all of these records have been audited. And I should further add that I have known many of those who have invested with these managers, and the checks received by those participants over the years have matched the stated records.

Before we begin this examination, I would like you to imagine a national coin-flipping contest. Let's assume we get 225 million Americans up tomorrow morning and we ask them all to wager a dollar. They go out in the morning at sunrise, and they all call the flip of a coin. If they call correctly, they win a dollar from those who called wrong. Each day the losers drop out, and on the subsequent day the stakes build as all previous winnings are put on the line. After ten flips on ten mornings, there will be approximately 220,000 people in the United States who have correctly called ten flips in a row. They each will have won a little over $1,000.

Now this group will probably start getting a little puffed up about this, human nature being what it is. They may try to be modest, but at cocktail parties they will occasionally admit to attractive members of the opposite sex what their technique is, and what marvellous insights they bring to the field of flipping.

Assuming that the winners are getting the appropriate rewards from the losers, in another ten days we will have 215 people who have successfully called their coin flips 20 times in a row and who, by this exercise, each have turned one dollar into a little over $1 million. $225 million would have been lost, $225 million would have been won.

By then, this group will really lose their heads. They will probably write books on "How I turned a Dollar into a Million in Twenty Days Working Thirty Seconds a Morning." Worse yet, they'll probably start jetting around the country attending seminars on efficient coin-flipping and tackling sceptical professors with, " If it can't be done, why are there 215 of us?"

By then some business school professor will probably be rude enough to bring up the fact that if 225 million orangutans had engaged in a similar exercise, the results would be much the same - 215 egotistical orangutans with 20 straight winning flips.

I would argue, however, that there are some important differences in the examples I am going to present. For one thing, if

a) you had taken 225 million orangutans distributed roughly as the U.S. population is; if

b) 215 winners were left after 20 days; and if

c) you found that 40 came from a particular zoo in Omaha, you would be pretty sure you were on to something.

So you would probably go out and ask the zoo keeper about what he's feeding them, whether they had special exercises, what books they read, and who knows what else. That is, if you found any really extraordinary concentrations of success, you might want to see if you could identify concentrations of unusual characteristics that might be causal factors.

Scientific inquiry naturally follows such a pattern. If you were trying to analyze possible causes of a rare type of cancer -- with, say, 1,500 cases a year in the United States -- and you found that 400 of them occurred in some little mining town in Montana, you would get very interested in the water there, or the occupation of those afflicted, or other variables. You know it's not random chance that 400 come from a small area. You would not necessarily know the causal factors, but you would know where to search.

I submit to you that there are ways of defining an origin other than geography. In addition to geographical origins, there can be what I call an intellectual origin. I think you will find that a disproportionate number of successful coin-flippers in the investment world came from a very small intellectual village that could be called Graham-and-Doddsville. A concentration of winners that simply cannot be explained by chance can be traced to this particular intellectual village.

Conditions could exist that would make even that concentration unimportant. Perhaps 100 people were simply imitating the coin-flipping call of some terribly persuasive personality. When he called heads, 100 followers automatically called that coin the same way. If the leader was part of the 215 left at the end, the fact that 100 came from the same intellectual origin would mean nothing. You would simply be identifying one case as a hundred cases. Similarly, let's assume that you lived in a strongly patriarchal society and every family in the United States conveniently consisted of ten members. Further assume that the patriarchal culture was so strong that, when the 225 million people went out the first day, every member of the family identified with the father's call. Now, at the end of the 20-day period, you would have 215 winners, and you would find that they came from only 21.5 families. Some naive types might say that this indicates an enormous hereditary factor as an explanation of successful coin-flipping. But, of course, it would have no significance at all because it would simply mean that you didn't have 215 individual winners, but rather 21.5 randomly distributed families who were winners.

In this group of successful investors that I want to consider, there has been a common intellectual patriarch, Ben Graham. But the children who left the house of this intellectual patriarch have called their "flips" in very different ways. They have gone to different places and bought and sold different stocks and companies, yet they have had a combined record that simply cannot be explained by the fact that they are all calling flips identically because a leader is signalling the calls for them to make. The patriarch has merely set forth the intellectual theory for making coin-calling decisions, but each student has decided on his own manner of applying the theory.

The common intellectual theme of the investors from Graham-and-Doddsville is this: they search for discrepancies between the value of a business and the price of small pieces of that business in the market. Essentially, they exploit those discrepancies without the efficient market theorist's concern as to whether the stocks are bought on Monday or Thursday, or whether it is January or July, etc. Incidentally, when businessmen buy businesses, which is just what our Graham & Dodd investors are doing through the purchase of marketable stocks -- I doubt that many are cranking into their purchase decision the day of the week or the month in which the transaction is going to occur. If it doesn't make any difference whether all of a business is being bought on a Monday or a Friday, I am baffled why academicians invest extensive time and effort to see whether it makes a difference when buying small pieces of those same businesses. Our Graham & Dodd investors, needless to say, do not discuss beta, the capital asset pricing model, or covariance in returns among securities. These are not subjects of any interest to them. In fact, most of them would have difficulty defining those terms. The investors simply focus on two variables: price and value.

I always find it extraordinary that so many studies are made of price and volume behavior, the stuff of chartists. Can you imagine buying an entire business simply because the price of the business had been marked up substantially last week and the week before? Of course, the reason a lot of studies are made of these price and volume variables is that now, in the age of computers, there are almost endless data available about them. It isn't necessarily because such studies have any utility; it's simply that the data are there and academicians have [worked] hard to learn the mathematical skills needed to manipulate them. Once these skills are acquired, it seems sinful not to use them, even if the usage has no utility or negative utility. As a friend said, to a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

I think the group that we have identified by a common intellectual home is worthy of study. Incidentally, despite all the academic studies of the influence of such variables as price, volume, seasonality, capitalization size, etc., upon stock performance, no interest has been evidenced in studying the methods of this unusual concentration of value-oriented winners.

I begin this study of results by going back to a group of four of us who worked at Graham-Newman Corporation from 1954 through 1956. There were only four -- I have not selected these names from among thousands. I offered to go to work at Graham-Newman for nothing after I took Ben Graham's class, but he turned me down as overvalued. He took this value stuff very seriously! After much pestering he finally hired me. There were three partners and four of us as the "peasant" level. All four left between 1955 and 1957 when the firm was wound up, and it's possible to trace the record of three.

The first example (see Table 1) is that of Walter Schloss. Walter never went to college, but took a course from Ben Graham at night at the New York Institute of Finance. Walter left Graham-Newman in 1955 and achieved the record shown here over 28 years. Here is what "Adam Smith" -- after I told him about Walter -- wrote about him in Supermoney (1972):

He has no connections or access to useful information. Practically no one in Wall Street knows him and he is not fed any ideas. He looks up the numbers in the manuals and sends for the annual reports, and that's about it.

In introducing me to (Schloss) Warren had also, to my mind, described himself. "He never forgets that he is handling other people's money, and this reinforces his normal strong aversion to loss." He has total integrity and a realistic picture of himself. Money is real to him and stocks are real -- and from this flows an attraction to the "margin of safety" principle.

Walter has diversified enormously, owning well over 100 stocks currently. He knows how to identify securities that sell at considerably less than their value to a private owner. And that's all he does. He doesn't worry about whether it's January, he doesn't worry about whether it's Monday, he doesn't worry about whether it's an election year. He simply says, if a business is worth a dollar and I can buy it for 40 cents, something good may happen to me. And he does it over and over and over again. He owns many more stocks than I do -- and is far less interested in the underlying nature of the business; I don't seem to have very much influence on Walter. That's one of his strengths; no one has much influence on him.

The second case is Tom Knapp, who also worked at Graham-Newman with me. Tom was a chemistry major at Princeton before the war; when he came back from the war, he was a beach bum. And then one day he read that Dave Dodd was giving a night course in investments at Columbia. Tom took it on a non-credit basis, and he got so interested in the subject from taking that course that he came up and enrolled at Columbia Business School, where he got the MBA degree. He took Dodd's course again, and took Ben Graham's course. Incidentally, 35 years later I called Tom to ascertain some of the facts involved here and I found him on the beach again. The only difference is that now he owns the beach!

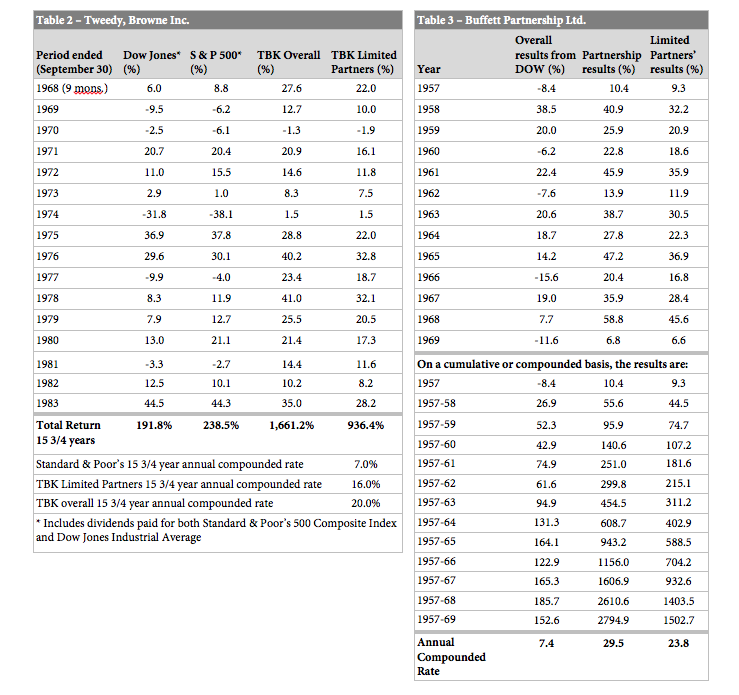

In 1968, Tom Knapp and Ed Anderson, also a Graham disciple, along with one or two other fellows of similar persuasion, formed Tweedy, Browne Partners, and their investment results appear in Table 2. Tweedy, Browne built that record with very wide diversification. They occasionally bought control of businesses, but the record of the passive investments is equal to the record of the control investments.

Table 3 describes the third member of the group who formed Buffett Partnership in 1957. The best thing he did was to quit in 1969. Since then, in a sense, Berkshire Hathaway has been a continuation of the partnership in some respects. There is no single index I can give you that I would feel would be a fair test of investment management at Berkshire. But I think that any way you figure it, it has been satisfactory.

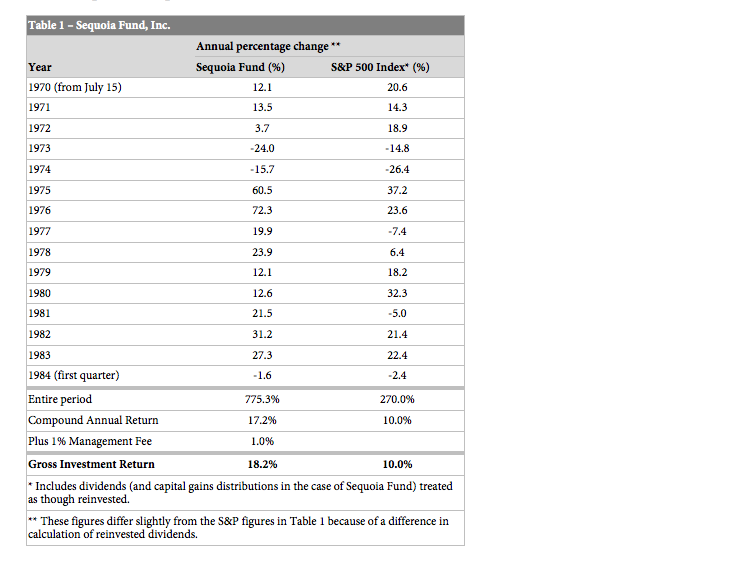

Table 4 shows the record of the Sequoia Fund, which is managed by a man whom I met in 1951 in Ben Graham's class, Bill Ruane. After getting out of Harvard Business School, he went to Wall Street. Then he realized that he needed to get a real business education so he came up to take Ben's course at Columbia, where we met in early 1951. Bill's record from 1951 to 1970, working with relatively small sums, was far better than average. When I wound up Buffett Partnership I asked Bill if he would set up a fund to handle all our partners, so he set up the Sequoia Fund. He set it up at a terrible time, just when I was quitting. He went right into the two-tier market and all the difficulties that made for comparative performance for value-oriented investors. I am happy to say that my partners, to an amazing degree, not only stayed with him but added money, with the happy result shown here.

There's no hindsight involved here. Bill was the only person I recommended to my partners, and I said at the time that if he achieved a four-point-per-annum advantage over the Standard & Poor's, that would be solid performance. Bill has achieved well over that, working with progressively larger sums of money. That makes things much more difficult. Size is the anchor of performance. There is no question about it. It doesn't mean you can't do better than average when you get larger, but the margin shrinks. And if you ever get so you're managing two trillion dollars, and that happens to be the amount of the total equity valuation in the economy, don't think that you'll do better than average!

I should add that in the records we've looked at so far, throughout this whole period there was practically no duplication in these portfolios. These are men who select securities based on discrepancies between price and value, but they make their selections very differently. Walter's largest holdings have been such stalwarts as Hudson Pulp & Paper and Jeddo Highland Coal and New York Trap Rock Company and all those other names that come instantly to mind to even a casual reader of the business pages. Tweedy Browne's selections have sunk even well below that level in terms of name recognition. On the other hand, Bill has worked with big companies. The overlap among these portfolios has been very, very low. These records do not reflect one guy calling the flip and fifty people yelling out the same thing after him.

Table 5 is the record of a friend of mine who is a Harvard Law graduate, who set up a major law firm. I ran into him in about 1960 and told him that law was fine as a hobby but he could do better. He set up a partnership quite the opposite of Walter's. His portfolio was concentrated in very few securities and therefore his record was much more volatile but it was based on the same discount-from-value approach. He was willing to accept greater peaks and valleys of performance, and he happens to be a fellow whose whole psyche goes toward concentration, with the results shown. Incidentally, this record belongs to Charlie Munger, my partner for a long time in the operation of Berkshire Hathaway. When he ran his partnership, however, his portfolio holdings were almost completely different from mine and the other fellows mentioned earlier.

Table 6 is the record of a fellow who was a pal of Charlie Munger's -- another non-business school type -- who was a math major at USC. He went to work for IBM after graduation and was an IBM salesman for a while. After I got to Charlie, Charlie got to him. This happens to be the record of Rick Guerin. Rick, from 1965 to 1983, against a compounded gain of 316 percent for the S&P, came off with 22,200 percent, which probably because he lacks a business school education, he regards as statistically significant.

One sidelight here: it is extraordinary to me that the idea of buying dollar bills for 40 cents takes immediately to people or it doesn't take at all. It's like an inoculation. If it doesn't grab a person right away, I find that you can talk to him for years and show him records, and it doesn't make any difference. They just don't seem able to grasp the concept, simple as it is. A fellow like Rick Guerin, who had no formal education in business, understands immediately the value approach to investing and he's applying it five minutes later. I've never seen anyone who became a gradual convert over a ten-year period to this approach. It doesn't seem to be a matter of IQ or academic training. It's instant recognition, or it is nothing.

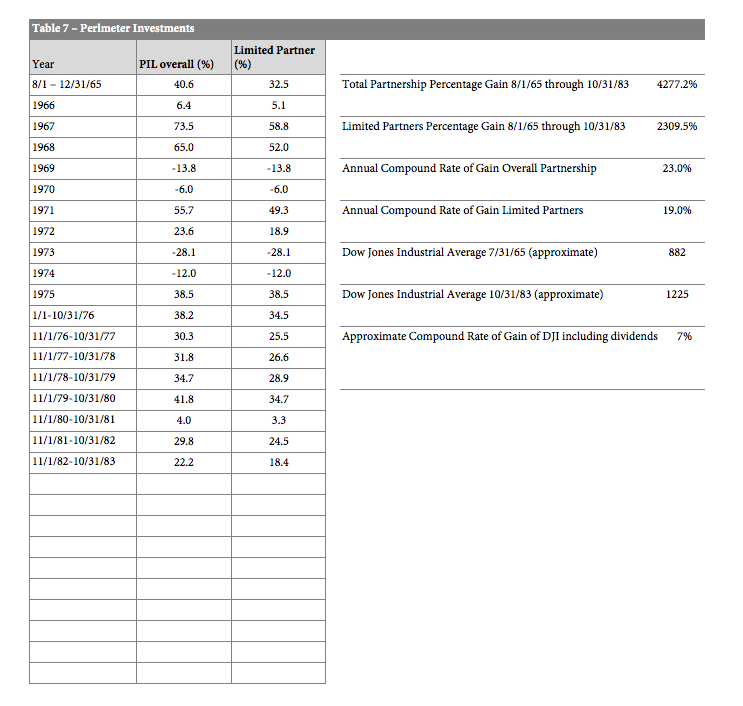

Table 7 is the record of Stan Perimeter. Stan was a liberal arts major at the University of Michigan who was a partner in the advertising agency of Bozell & Jacobs. We happened to be in the same building in Omaha. In 1965 he figured out I had a better business than he did, so he left advertising. Again, it took five minutes for Stan to embrace the value approach.

Perimeter does not own what Walter Schloss owns. He does not own what Bill Ruane owns. These are records made independently. But every time Perimeter buys a stock it's because he's getting more for his money than he's paying. That's the only thing he's thinking about. He's not looking at quarterly earnings projections, he's not looking at next year's earnings, he's not thinking about what day of the week it is, he doesn't care what investment research from any place says, he's not interested in price momentum, volume, or anything. He's simply asking: what is the business worth?

Table 8 and Table 9 are the records of two pension funds I've been involved in. They are not selected from dozens of pension funds with which I have had involvement; they are the only two I have influenced. In both cases I have steered them toward value-oriented managers. Very, very few pension funds are managed from a value standpoint. Table 8 is the Washington Post Company's Pension Fund. It was with a large bank some years ago, and I suggested that they would do well to select managers who had a value orientation.

As you can see, overall they have been in the top percentile ever since they made the change. The Post told the managers to keep at least 25 percent of these funds in bonds, which would not have been necessarily the choice of these managers. So I've included the bond performance simply to illustrate that this group has no particular expertise about bonds. They wouldn't have said they did. Even with this drag of 25 percent of their fund in an area that was not their game, they were in the top percentile of fund management. The Washington Post experience does not cover a terribly long period but it does represent many investment decisions by three managers who were not identified retroactively.

Table 9 is the record of the FMC Corporation fund. I don't manage a dime of it myself but I did, in 1974, influence their decision to select value-oriented managers. Prior to that time they had selected managers much the same way as most larger companies. They now rank number one in the Becker survey of pension funds for their size over the period of time subsequent to this "conversion" to the value approach. Last year they had eight equity managers of any duration beyond a year. Seven of them had a cumulative record better than the S&P. The net difference now between a median performance and the actual performance of the FMC fund over this period is $243 million. FMC attributes this to the mindset given to them about the selection of managers. Those managers are not the managers I would necessarily select but they have the common denominators of selecting securities based on value.

So these are nine records of "coin-flippers" from Graham-and-Doddsville. I haven't selected them with hindsight from among thousands. It's not like I am reciting to you the names of a bunch of lottery winners -- people I had never heard of before they won the lottery. I selected these men years ago based upon their framework for investment decision-making. I knew what they had been taught and additionally I had some personal knowledge of their intellect, character, and temperament. It's very important to understand that this group has assumed far less risk than average; note their record in years when the general market was weak. While they differ greatly in style, these investors are, mentally, always buying the business, not buying the stock. A few of them sometimes buy whole businesses. Far more often they simply buy small pieces of businesses. Their attitude, whether buying all or a tiny piece of a business, is the same. Some of them hold portfolios with dozens of stocks; others concentrate on a handful. But all exploit the difference between the market price of a business and its intrinsic value.

I'm convinced that there is much inefficiency in the market. These Graham-and-Doddsville investors have successfully exploited gaps between price and value. When the price of a stock can be influenced by a "herd" on Wall Street with prices set at the margin by the most emotional person, or the greediest person, or the most depressed person, it is hard to argue that the market always prices rationally. In fact, market prices are frequently nonsensical.

I would like to say one important thing about risk and reward. Sometimes risk and reward are correlated in a positive fashion. If someone were to say to me, "I have here a six-shooter and I have slipped one cartridge into it. Why don't you just spin it and pull it once? If you survive, I will give you $1 million." I would decline -- perhaps stating that $1 million is not enough. Then he might offer me $5 million to pull the trigger twice -- now that would be a positive correlation between risk and reward!

The exact opposite is true with value investing. If you buy a dollar bill for 60 cents, it's riskier than if you buy a dollar bill for 40 cents, but the expectation of reward is greater in the latter case. The greater the potential for reward in the value portfolio, the less risk there is.

One quick example: The Washington Post Company in 1973 was selling for $80 million in the market. At the time, that day, you could have sold the assets to any one of ten buyers for not less than $400 million, probably appreciably more. The company owned the Post, Newsweek, plus several television stations in major markets. Those same properties are worth $2 billion now, so the person who would have paid $400 million would not have been crazy.

Now, if the stock had declined even further to a price that made the valuation $40 million instead of $80 million, its beta would have been greater. And to people that think beta measures risk, the cheaper price would have made it look riskier. This is truly Alice in Wonderland. I have never been able to figure out why it's riskier to buy $400 million worth of properties for $40 million than $80 million. And, as a matter of fact, if you buy a group of such securities and you know anything at all about business valuation, there is essentially no risk in buying $400 million for $80 million, particularly if you do it by buying ten $40 million piles of $8 million each. Since you don't have your hands on the $400 million, you want to be sure you are in with honest and reasonably competent people, but that's not a difficult job.

You also have to have the knowledge to enable you to make a very general estimate about the value of the underlying businesses. But you do not cut it close. That is what Ben Graham meant by having a margin of safety. You don't try and buy businesses worth $83 million for $80 million. You leave yourself an enormous margin. When you build a bridge, you insist it can carry 30,000 pounds, but you only drive 10,000 pound trucks across it. And that same principle works in investing.

In conclusion, some of the more commercially minded among you may wonder why I am writing this article. Adding many converts to the value approach will perforce narrow the spreads between price and value. I can only tell you that the secret has been out for 50 years, ever since Ben Graham and Dave Dodd wrote Security Analysis, yet I have seen no trend toward value investing in the 35 years that I've practiced it. There seems to be some perverse human characteristic that likes to make easy things difficult. The academic world, if anything, has actually backed away from the teaching of value investing over the last 30 years. It's likely to continue that way. Ships will sail around the world but the Flat Earth Society will flourish. There will continue to be wide discrepancies between price and value in the marketplace, and those who read their Graham & Dodd will continue to prosper.

Warren E. Buffett, is chairman and chief executive officer of Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. an Omaha-based insurer with major holdings in several other industries, including General Foods, Xerox and Washington Post Company

After getting an A+ in Benjamin Graham’s class and graduating from Columbia Business School in 1951, Buffett went to work on Wall Street at Graham Newman & Company. In 1957, founded his own partnership which he ran for ten years. This article is based on a speech he gave at Columbia Business School, May 17, 1984 at a seminar marking the 50th anniversary of the publication of Benjamin Graham and David Dodd’s Security Analysis.

Risk Revisited

Memo to: Oaktree Clients

From: Howard Marks

Re: Risk Revisited

In April I had good results with Dare to Be Great II, starting from the base established in an earlier memo (Dare to Be Great, September 2006) and adding new thoughts that had occurred to me in the intervening years. Also in 2006 I wrote Risk, my first memo devoted entirely to this key subject. My thinking continued to develop, causing me to dedicate three chapters to risk among the twenty in my book The Most Important Thing. This memo adds to what I’ve previously written on the topic.

What Risk Really Means

In the 2006 memo and in the book, I argued against the purported identity between volatility and risk. Volatility is the academic’s choice for defining and measuring risk. I think this is the case largely because volatility is quantifiable and thus usable in the calculations and models of modern finance theory. In the book I called it “machinable,” and there is no substitute for the purposes of the calculations.

However, while volatility is quantifiable and machinable – and can also be an indicator or symptom of riskiness and even a specific form of risk – I think it falls far short as “the” definition of investment risk. In thinking about risk, we want to identify the thing that investors worry about and thus demand compensation for bearing. I don’t think most investors fear volatility. In fact, I’ve never heard anyone say, “The prospective return isn’t high enough to warrant bearing all that volatility.” What they fear is the possibility of permanent loss.

Permanent loss is very different from volatility or fluctuation. A downward fluctuation – which by definition is temporary – doesn’t present a big problem if the investor is able to hold on and come out the other side. A permanent loss – from which there won’t be a rebound – can occur for either of two reasons: (a) an otherwise-temporary dip is locked in when the investor sells during a downswing – whether because of a loss of conviction; requirements stemming from his timeframe; financial exigency; or emotional pressures, or (b) the investment itself is unable to recover for fundamental reasons. We can ride out volatility, but we never get a chance to undo a permanent loss.

Of course, the problem with defining risk as the possibility of permanent loss is that it lacks the very thing volatility offers: quantifiability. The probability of loss is no more measurable than the probability of rain. It can be modeled, and it can be estimated (and by experts pretty well), but it cannot be known.

In Dare to Be Great II, I described the time I spent advising a sovereign wealth fund about how to organize for the next thirty years. My presentation was built significantly around my conviction that risk can’t be quantified a priori. Another of their advisors, a professor from a business school north of New York, insisted it can. This is something I prefer not to debate, especially with people who’re sure they have the answer but haven’t bet much money on it.

One of the things the professor was sure could be quantified was the maximum a portfolio could fall under adverse circumstances. But how can this be so if we don’t know how adverse circumstances can be or how they will influence returns? We might say “the market probably won’t fall more than x% as long as things aren’t worse than y and z,” but how can an absolute limit be specified? I wonder if the professor had anticipated that the S&P 500 could fall 57% in the global crisis.

While writing the original memo on risk in 2006, an important thought came to me for the first time. Forget about a priori; if you define risk as anything other than volatility, it can’t be measured even after the fact. If you buy something for $10 and sell it a year later for $20, was it risky or not? The novice would say the profit proves it was safe, while the academic would say it was clearly risky, since the only way to make 100% in a year is by taking a lot of risk. I’d say it might have been a brilliant, safe investment that was sure to double or a risky dart throw that got lucky.

If you make an investment in 2012, you’ll know in 2014 whether you lost money (and how much), but you won’t know whether it was a risky investment – that is, what the probability of loss was at the time you made it. To continue the analogy, it may rain tomorrow, or it may not, but nothing that happens tomorrow will tell you what the probability of rain was as of today. And the risk of rain is a very good analogue (although I’m sure not perfect) for the risk of loss.

The Unknowable Future

It seems most people in the prediction business think the future is knowable, and all they have to do is be among the ones who know it. Alternatively, they may understand (consciously or unconsciously) that it’s not knowable but believe they have to act as if it is in order to make a living as an economist or investment manager.

On the other hand, I’m solidly convinced the future isn’t knowable. I side with John Kenneth Galbraith who said, “We have two classes of forecasters: Those who don’t know – and those who don’t know they don’t know.” There are several reasons for this inability to predict:

We’re well aware of many factors that can influence future events, such as governmental actions, individuals’ spending decisions and changes in commodity prices. But these things are hard to predict, and I doubt anyone is capable of taking all of them into account at once. (People have suggested a parallel between this categorization and that of Donald Rumsfeld, who might have called these things “known unknowns”: the things we know we don’t know.)

The future can also be influenced by events that aren’t on anyone’s radar today, such as calamities – natural or man-made – that can have great impact. The 9/11 attacks and the Fukushima disaster are two examples of things no one knew to think about. (These would be “unknown unknowns”: the things we don’t know we don’t know.)

There’s far too much randomness at work in the world for future events to be predictable. As 2014 began, forecasters were sure the U.S. economy was gaining steam, but they were confounded when record cold weather caused GDP to fall 2.9% in the first quarter.

And importantly, the connections between contributing influences and future outcomes are far too imprecise and variable for the results to be dependable.

That last point deserves discussion. Physics is a science, and for that reason an electrical engineer can guarantee you that if you flip a switch over here, a light will go on over there . . . every time. But there’s good reason why economics is called “the dismal science,” and in fact it isn’t much of a science at all. In just the last few years we’ve had opportunity to see – contrary to nearly unanimous expectations – that interest rates near zero can fail to produce a strong rebound in GDP, and that a reduction of bond buying on the part of the Fed can fail to bring on higher interest rates. In economics and investments, because of the key role played by human behaviour, you just can’t say for sure that “if A, then B,” as you can in real science. The weakness of the connection between cause and effect makes outcomes uncertain. In other words, it introduces risk.

Given the near-infinite number of factors that influence the future, the great deal of randomness present, and the weakness of the linkages, it’s my solid belief that future events cannot be predicted with any consistency. In particular, predictions of important divergences from trends and norms can’t be made with anything approaching the accuracy required for them to be helpful.

Coping with the Unknowable Future

Here’s the essential conundrum: investing requires us to decide how to position a portfolio for future developments, but the future isn’t knowable.

Taken to slightly greater detail:

Investing requires the taking of positions that will be affected by future developments.

The existence of negative possibilities surrounding those future developments presents risk.

Intelligent investors pursue prospective returns that they think compensate them for bearing the risk of negative future developments.

But future developments are unpredictable.How can investors deal with the limitations on their ability to know the future? The answer lies in the fact that not being able to know the future doesn’t mean we can’t deal with it. It’s one thing to know what’s going to happen and something very different to have a feeling for the range of possible outcomes and the likelihood of each one happening. Saying we can’t do the former doesn’t mean we can’t do the latter.

The information we’re able to estimate – the list of events that might happen and how likely each one is – can be used to construct a probability distribution. Key point number one in this memo is that the future should be viewed not as a fixed outcome that’s destined to happen and capable of being predicted, but as a range of possibilities and, hopefully on the basis of insight into their respective likelihoods, as a probability distribution.

Since the future isn’t fixed and future events can’t be predicted, risk cannot be quantified with any precision. I made the point in Risk, and I want to emphasize it here, that risk estimation has to be the province of experienced experts, and their work product will by necessity be subjective, imprecise, and more qualitative than quantitative (even if it’s expressed in numbers).

There’s little I believe in more than Albert Einstein’s observation: “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.” I’d rather have an order-of-magnitude approximation of risk from an expert than a precise figure from a highly educated statistician who knows less about the underlying investments. British philosopher and logician Carveth Read put it this way: “It is better to be vaguely right than exactly wrong.”

By the way, in my personal life I tend to incorporate another of Einstein’s comments: “I never think of the future – it comes soon enough.” We can’t take that approach as investors, however. We have to think about the future. We just shouldn’t accord too much significance to our opinions.

We can’t know what will happen. We can know something about the possible outcomes (and how likely they are). People who have more insight into these things than others are likely to make superior investors. As I said in the last paragraph of The Most Important Thing:

Only investors with unusual insight can regularly divine the probability distribution that governs future events and sense when the potential returns compensate for the risks that lurk in the distribution’s negative left-hand tail.

In other words, in order to achieve superior results, an investor must be able – with some regularity – to find asymmetries: instances when the upside potential exceeds the downside risk. That’s what successful investing is all about.

Thinking in Terms of Diverse Outcomes

It’s the indeterminate nature of future events that creates investment risk. It goes without saying that if we knew everything that was going to happen, there wouldn’t be any risk.

The return on a stock will be a function of the relationship between the price today and the cash flows (income and sale proceeds) it will produce in the future. The future cash flows, in turn, will be a function of the fundamental performance of the company and the way its stock is priced given that performance. We invest on the basis of expectations regarding these things. It’s tautological to say that if the company’s earnings and the valuation of those earnings meet our targets, the return will be as expected. The risk in the investment therefore comes from the possibility that one or both will come in lower than we think.

To oversimplify, investors in a given company may have an expectation that if A happens, that’ll make B happen, and if C and D also happen, then the result will be E. Factor A may be the pace at which a new product finds an audience. That will determine factor B, the growth of sales. If A is positive, B should be positive. Then if C (the cost of raw materials) is on target, earnings should grow as expected, and if D (investors’ valuation of the earnings) also meets expectations, the result should be a rising share price, giving us the return we seek (E).

We may have a sense for the probability distributions governing future developments, and thus a feeling for the likely outcome regarding each of developments A through E. The problem is that for each of these, there can be lots of outcomes other than the ones we consider most likely. The possibility of less- good outcomes is the source of risk. That leads me to my second key point, as expressed by Elroy Dimson, a professor at the London Business School: “Risk means more things can happen than will happen.” This brief, pithy sentence contains a great deal of wisdom.

Here’s how I put it in No Different This Time – The Lessons of ’07 (December 2007):

No ambiguity is evident when we view the past. Only the things that happened happened. But that definiteness doesn’t mean the process that creates outcomes is clear-cut and dependable. Many things could have happened in each case in the past, and the fact that only one did happen understates the variability that existed. What I mean to say (inspired by Nicolas Nassim Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness) is that the history that took place is only one version of what it could have been. If you accept this, then the relevance of history to the future is much more limited than may appear to be the case.

People who rely heavily on forecasts seem to think there’s only one possibility, meaning risk can be eliminated if they just figure out which one it is. The rest of us know many possibilities exist today, and it’s not knowable which of them will occur. Further, things are subject to change, meaning there will be new possibilities tomorrow. This uncertainty as to which of the possibilities will occur is the source of risk in investing.

Even a Probability Distribution isn't Enough

I’ve stressed the importance of viewing the future as a probability distribution rather than a single predetermined outcome. It’s still essential to bear in mind key point number three: Knowing the probabilities doesn’t mean you know what’s going to happen. For example, every good backgammon player knows the probabilities governing throws of the dice. They know there are 36 possible outcomes, and that six of them add up to the number seven (1-6, 2-5, 3-4, 4-3, 5-2 and 6-1). Thus the chance of throwing a seven on any toss is 6 in 36, or 16.7%. There’s absolutely no doubt about that. But even though we know the probability of each number, we’re far from knowing what number will come up on a given roll.

Backgammon players are usually quite happy to make a move that will enable them to win unless the opponent rolls twelve, since only one combination of the dice will produce it: 6-6. The probability of rolling twelve is thus only 1 in 36, or less than 3%. But twelve does come up from time to time, and the people it turns into losers end up complaining about having done the “right” thing but lost. As my friend Bruce Newberg says, “There’s a big difference between probability and outcome.” Unlikely things happen – and likely things fail to happen – all the time. Probabilities are likelihoods and very far from certainties.

It’s true with dice, and it’s true in investing . . . and not a bad start toward conveying the essence of risk. Think again about the quote above from Elroy Dimson: “Risk means more things can happen than will happen.” I find it particularly helpful to invert Dimson’s observation for key point number four: Even though many things can happen, only one will.

In Dare to Be Great II, I discussed the fact that economic decisions are usually best made on the basis of “expected value”: you multiply each potential outcome by its probability, sum the results, and select the path with the highest total. But while expected value weights all of the possible outcomes on the basis of their likelihood, there may be some individual outcomes that absolutely cannot be tolerated. Even though many things can happen, only one will . . . and if something unacceptable can happen on the path with the highest expected value, we may not be able to choose on that basis. We may have to shun that path in order to avoid the extreme negative outcome. I always say I have no interest in being a skydiver who’s successful 95% of the time.

Investment performance (like life in general) is a lot like choosing a lottery winner by pulling one ticket from a bowlful. The process through which the winning ticket is chosen can be influenced by physical processes, and also by randomness. But it never amounts to anything but one ticket picked from among many. Superior investors have a better sense for the tickets in the bowl, and thus for whether it’s worth buying a ticket in a lottery. Lesser investors have less of a sense for the probability distribution and for whether the likelihood of winning the prize compensates for the risk that the cost of the ticket will be lost.

Risk and Return

Both in the 2006 memo on risk and in my book, I showed two graphics that together make clear the nature of investment risk. People have told me they’re the best thing in the book, and since readers of this memo might have not seen the old one or read the book, I’m going to repeat them here.

The first one below shows the relationship between risk and return as it is conventionally represented. The line slopes upward to the right, meaning the two are “positively correlated”: as risk increases, return increases.

In both the old memo and the book, I went to great lengths to clarify what this is often – but erroneously – taken to mean. We hear it all the time: “Riskier investments produce higher returns” and “If you want to make more money, take more risk.”

Both of these formulations are terrible. In brief, if riskier investments could be counted on to produce higher returns, they wouldn’t be riskier. Misplaced reliance on the benefits of risk bearing has led investors to some very unpleasant surprises.

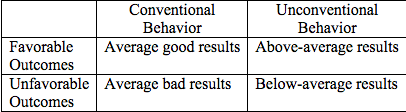

However, there’s another, better way to describe this relationship: “Investments that seem riskier have to appear likely to deliver higher returns, or else people won’t make them.” This makes perfect sense. If the market is rational, the price of a seemingly risky asset will be set low enough that the reward for holding it seems adequate to compensate for the risk present. But note the word “appear.” We’re talking about investors’ opinions regarding future return, not facts. Risky investments are – by definition – far from certain to deliver on their promise of high returns. For that reason, I think the graphic below does a much better job of portraying reality:

Here the underlying relationship between risk and return reflects the same positive general tendency as the first graphic, but the result of each investment is shown as a range of possibilities, not the single outcome suggested by the upward-sloping line. At each point along the horizontal risk axis, an investment’s prospective return is shown as a bell-shaped probability distribution turned on its side.

The conclusions are obvious from inspection. As you move to the right, increasing the risk:

the expected return increases (as with the traditional graphic),

the range of possible outcomes becomes wider, and

the less-good outcomes become worse.

This is the essence of investment risk. Riskier investments are ones where the investor is less secure regarding the eventual outcome and faces the possibility of faring worse than those who stick to safer investments, and even of losing money. These investments are undertaken because the expected return is higher. But things may happen other than that which is hoped for. Some of the possibilities are superior to the expected return, but others are decidedly unattractive.

The first graph’s upward-sloping line indicates the underlying directionality of the risk/return relationship. But there’s a lot more to consider than the fact that expected returns rise along with perceived risk, and in that regard the first graph is highly misleading. The second graph shows both the underlying trend and the increasing potential for actual returns to deviate from expectations. While the expected return rises along with risk, so does the probability of lower returns . . . and even of losses. This way of looking at things reflects Professor Dimson’s dictum that more than one thing can happen. That’s reality in an unpredictable world.

The Many Forms of Risk

The possibility of permanent loss may be the main risk in investing, but it’s not the only risk. I can think of lots of other risks, many of which contribute to – or are components of – that main risk.

In the past, in addition to the risk of permanent loss, I’ve mentioned the risk of falling short. Some investors face return requirements in order to make necessary payouts, as in the case of pension funds, endowments and insurance companies. Others have more basic needs, like generating enough income to live on.

Some investors with needs – particularly those who live on their income, and especially in today’s low- return environment – face a serious conundrum. If they put their money into safe investments, their returns may be inadequate. But if they take on incremental risk in pursuit of a higher return, they face the possibility of a still-lower return, and perhaps of permanent diminution of their capital, rendering their subsequent income lower still. There’s no easy way to resolve this conundrum.

There are actually two possible causes of inadequate returns: (a) targeting a high return and being thwarted by negative events and (b) targeting a low return and achieving it. In other words, investors face not one but two major risks: the risk of losing money and the risk of missing opportunities. Either can be eliminated but not both. And leaning too far in order to avoid one can set you up to be victimized by the other.

Potential opportunity costs – the result of missing opportunities – usually aren’t taken as seriously as real potential losses. But they do deserve attention. Put another way, we have to consider the risk of not taking enough risk.

These days, the fear of losing money seems to have receded (since the crisis is all of six years in the past), and the fear of missing opportunities is riding high, given the paltry returns available on safe, mundane investments. Thus a new risk has arisen: FOMO risk, or the risk that comes from excessive fear of missing out. It’s important to worry about missing opportunities, since people who don’t can invest too conservatively. But when that worry becomes excessive, FOMO can drive an investor to do things he shouldn’t do and often doesn’t understand, just because others are doing them: if he doesn’t jump on the bandwagon, he may be left behind to live with envy.

Over the last three years, Oaktree’s response to the paucity of return has been to develop a suite of five credit strategies that we hope will produce a 10% return, either net or gross (we can’t claim to be more precise than that). I call them collectively the “ten percent solution,” after a Sherlock Holmes story called The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (we aim to do better). Talking to clients about these strategies and helping them choose between them has required me to focus on their risks.

“Just a minute,” you might say, “the ten-year Treasury is paying just 21⁄2% and, as Jeremy Grantham says, the risk-free rate is also return-free. How, then, can you target returns in the vicinity of 10%?” The answer is that it can’t be done without taking risk of some kind – and there are several candidates. I’ll list below a few risks that we’re consciously bearing in order to generate the returns our clients desire:

Today’s ultra-low interest rates imply low returns for anyone who invests in what are deemed safe fixed income instruments. So Oaktree’s pursuit of attractive returns centers on accepting and managing credit risk, or the risk that a borrower will be unable to pay interest and repay principal as scheduled. Treasury's are assumed to be free of credit risk, and most high grade corporates are thought to be nearly so. Thus those who intelligently accept incremental credit risk must do so with the expectation that the incremental return promised as compensation will prove sufficient. Voluntarily accepting credit risk has been at the core of what Oaktree has done since its beginning in 1995 (and in fact since the seed was planted in 1978, when I initiated Citibank’s high yield bond effort). But bearing credit risk will lead to attractive returns only if it’s done well. Our activities are based on two beliefs: (a) that because the investing establishment is averse to credit risk, the incremental returns we receive for bearing it will compensate generously for the risk entailed and (b) that credit risk is manageable – i.e., unlike the general future, credit risk can be gauged by experts (like us) and reduced through credit selection. It wouldn’t make sense to voluntarily bear incremental credit risk if either of these two beliefs were lacking.

Another way to access attractive returns in today’s low-rate environment is to bear illiquidity risk in order to take advantage of investors’ normal dislike for illiquidity (superior returns often follow from investor aversion). Institutions that held a lot of illiquid assets suffered considerably in the crisis of 2008, when they couldn’t sell them; thus many developed a strong aversion to them and in some cases imposed limitations on their representation in portfolios. Additionally, today the flow of retail money is playing a big part in driving up asset prices and driving down returns. Since retail money has a harder time making its way to illiquid assets, this has made the returns on the latter appear more attractive. It’s noteworthy that there aren’t mutual funds or ETFs for many of the things we’re investing in.

Some strategies introduce it voluntarily and some can’t get away from it: concentration risk. “Everyone knows” diversification is a good thing, since it reduces the impact on results of a negative development. But some people eschew the safety that comes with diversification in favour of concentrating their investments in assets or with managers they expect to outperform. And some investment strategies don’t permit full diversification because of the limitations of their subject markets. Thus problems – if and when they occur – will be bigger per se.

Especially given today’s low interest rates, borrowing additional capital to enhance returns is another way to potentially increase returns. But doing so introduces leverage risk. Leverage adds to risk two ways. The first is magnification: people are attracted to leverage because it will magnify gains, but under unfavorable outcomes it will magnify losses instead. The second way in which leverage adds to risk stems from funding risk, one of the classic reasons for financial disaster. The stage is set when someone borrows short-term funds to make a long-term investment. If the funds have to be repaid at an awkward time – due to their maturity, a margin call, or some other reason – and the purchased assets can’t be sold in a timely fashion (or can only be sold at a depressed price), an investment that might otherwise have been successful can be cut short and end in sorrow. Little or nothing may remain of the sale proceeds once the leverage has been repaid, in which case the investor’s equity will be decimated. This is commonly called a meltdown. It’s the primary reason for the saying, “Never forget the six-foot- tall man who drowned crossing the stream that was five feet deep on average.” In times of crisis, success over the long run can become irrelevant.

- When credit risk, illiquidity risk, concentration risk and leverage risk are borne intelligently, it is in the hope that the investor’s skill will be sufficient to produce success. If so, the potential incremental returns that appear to be offered as risk compensation will turn into realized incremental returns (per the graphic at the top of page 6). That’s the only reason anyone would do these things. As the graphic at the bottom of page 6 illustrates, however, investing further out on the risk curve exposes one to a broader range of investment outcomes. In an efficient market, returns are tethered to the market average; in an inefficient market, they’re not. Inefficient markets offer the possibility that an investor will escape from the “gravitational pull” of the market’s average return, but that can be either for the better or for the worse. Superior investors – those with “alpha,” or the personal skill needed to achieve outsized returns for a given level of risk – have scope to perform well above the mean return, while inferior investors can come out far below. So hiring an investment manager introduces manager risk: the risk of picking the wrong one. It’s possible to pay management fees but get decisions that detract from results rather than add.

Some or all of the above risks are potentially entailed in our new credit strategies. Parsing them allows investors to choose among the strategies and accept the risks they’re more comfortable with. The process can be quite informative.

Our oldest “new strategy” is Enhanced Income, where we use leverage to magnify the return from a portfolio of senior loans. We think senior loans have the lowest credit risk of anything Oaktree deals with, since they’re senior-most among their issuer’s debt and historically have produced very few credit losses. Further, they’re among our most liquid assets, meaning we face relatively little illiquidity risk, and being active in a broad public market permits us to diversify, reducing concentration risk. Given the relatively high degree of safety stemming from these loans’ seniority, returns aren’t overly dependent on the presence of alpha, meaning Enhanced Income entails less manager risk than some other strategies. But to have a chance at the healthy return we’re pursuing in Enhanced Income requires us to take some risk, and what we’re left with is leverage risk. The 3-to-1 leverage in Enhanced Income Fund II will magnify the negative impact of any credit losses (of course we hope there won’t be many). However, we’re not worried about a meltdown, since the current environment allows us to avoid funding risk; we can (a) borrow for a term that exceeds the duration of the underlying investments and (b) do so without the threat of margin calls related to price declines.

Strategic Credit, Mezzanine Finance, European Private Debt and Real Estate Debt are the other four components of our “ten percent solution.”

All four entail some degree of credit risk, illiquidity risk (they all invest heavily or entirely in private debt) and concentration risk (as their market niches offer only a modest number of investment opportunities, and securing them in today’s competitive environment is a challenge).

The Real Estate Debt Fund can only lever up to 1-to-1, and the other three borrow only small amounts and for short-term purposes, so none of them entails significant leverage risk.

- However, in order to succeed they’ll all require a high level of skill from their managers in identifying return prospects and keeping risk under control. Thus they all entail manager risk. Our response is to entrust these portfolios only to managers who’ve been with us for years.

It’s reasonable – essential, really – to study the risk entailed in every investment and accept the amounts and types of risk that you’re comfortable with (assuming this can be discerned). It’s not reasonable to expect highly superior returns without bearing some incremental risk.

I touched above on concentration risk, but we should also think about the flip side: the risk of over- diversification. If you have just a few holdings in a portfolio, or if an institution employs just a few managers, one bad decision can do significant damage to results. But if you have a very large number of holdings or managers, no one of them can have much of a positive impact on performance. Nobody invests in just the one stock or manager they expect to perform best, but as the number of positions is expanded, the standards for inclusion may decline. Peter Lynch coined the term “diworstification” to describe the process through which lesser investments are added to portfolios, making the potential risk- adjusted return worse.

While I don’t think volatility and risk are synonymous, there’s no doubt that volatility does present risk. If circumstances cause you to sell a volatile investment at the wrong time, you might turn a downward fluctuation into a permanent loss. Moreover, even in the absence of a need for liquidity, volatility can prey on investors’ emotions, reducing the probability they’ll do the right thing. And in the short run, it can be very hard to differentiate between a downward fluctuation and a permanent loss. Often this can really be done only in retrospect. Thus it’s clear that a professional investor may have to bear consequences for a temporary downward fluctuation simply because of its resemblance to a permanent loss. When you’re under pressure, the distinction between “volatility” and “loss” can seem only semantic. Volatility is not “the” definition of investment risk, as I said earlier, but it isn’t irrelevant.

One example of a risk connected with volatility – or the deviation of price from what might be intrinsic value – is basis risk. Arbitrageurs customarily set up positions where they’re long one asset and short a related asset. The two assets are expected to move roughly in parallel, except that the one that’s slightly cheaper should make more money for the investor in the long run than the other loses, producing a small net gain with little risk. Because these trades are considered so low in risk, they’re often levered up to the sky. But sometimes the prices of the two assets diverge to an unexpected extent, and the equity invested in the trade evaporates. That unexpected divergence is basis risk, and it’s what happened to Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, one of the most famous meltdowns of all time. As Long-Term’s chairman John Meriwether said at the time, “the Fund added to its positions in anticipation of convergence, yet . . . the trades diverged dramatically.” This benign-sounding explanation was behind a collapse some thought capable of bringing down the global financial system.

Long-Term’s failure was also attributable to model risk. Decisions can be turned over to quants or financial engineers who either (a) conclude wrongly that an unsystematic process can be modeled or (b) employ the wrong model. During the financial crisis, models often assumed that events would occur according to a “normal distribution,” but extreme “tail events” occurred much more often than the normal distribution says they will. Not only can extreme events exceed a model’s assumptions, but excessive belief in a model’s efficacy can induce people to take risks they would never take on the basis of qualitative judgement. They’re often disappointed to find they had put too much faith in a statistical sure thing.

Model risk can arise from black swan risk, for which I borrow the title of Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s popular second book. People tend to confuse “never been seen” with “impossible,” and the consequences can be dire when something occurs for the first time. That’s part of the reason why people lost so much in highly levered subprime mortgage securities. The fact that a nationwide spate of mortgage defaults hadn’t happened convinced investors that it couldn’t happen, and their certainty caused them to take actions so imprudent that it had to happen.

As long as we’re on the subject of things going wrong, we should touch on the subject of career risk. As I mentioned in Dare to Be Great II, “agents” who manage money for others can be penalized for investments that look like losers (that is, for both permanent losses and temporary downward fluctuations). Either of these unfortunate experiences can result in headline risk if the resulting losses are big enough to make it into the media, and some careers can’t withstand headline risk. Investors who lack the potential to share commensurately in investment successes face a reward asymmetry that can force them toward the safe end of the risk/return curve. They are likely to think more about the risk of losing money than about the risk of missing opportunities. Thus their portfolios may lean too far toward controlling risk and avoiding embarrassment (and they may not take enough chances to generate returns). There are consequences for these investors, as well as for those who employ them.

Event risk is another risk to worry about, something that was created by bond issuers about twenty years ago. Since corporate directors have a fiduciary responsibility to stockholders but not to bondholders, some think they can (and perhaps should) do anything that’s not explicitly prohibited to transfer value from bondholders to stockholders. Bondholders need covenants to shield them from this kind of pro- active plundering, but at times like today it can be hard to obtain strong protective covenants.

There are many ways for an investment to be unsuccessful. The two main ones are fundamental risk (relating to how a company or asset performs in the real world) and valuation risk (relating to how the market prices that performance). For years investors, fiduciaries and rule-makers acted on the belief that it’s safe to buy high-quality assets and risky to buy low-quality assets. But between 1968 and 1973, many investors in the “Nifty Fifty” (the stocks of the fifty fastest-growing and best companies in America) lost 80-90% of their money. Attitudes have evolved since then, and today there’s less of an assumption that high quality prevents fundamental risk, and much less preoccupation with quality for its own sake.

On the other hand, investors are more sensitive to the pivotal role played by price. At bottom, the riskiest thing is overpaying for an asset (regardless of its quality), and the best way to reduce risk is by paying a price that’s irrationally low (ditto). A low price provides a “margin of safety,” and that’s what risk-controlled investing is all about. Valuation risk should be easily combatted, since it’s largely within the investor’s control. All you have to do is refuse to buy if the price is too high given the fundamentals. “Who wouldn’t do that?” you might ask. Just think about the people who bought into the tech bubble.

Fundamental risk and valuation risk bear on the risk of losing money in an individual security or asset, but that’s far from the whole story. Correlation is the essential additional piece of the puzzle. Correlation is the degree to which an asset’s price will move in sympathy with the movements of others. The higher the correlation among its components, all other things being equal, the less effective diversification a portfolio has, and the more exposed it is to untoward developments.

An asset doesn’t have “a correlation.” Rather, it has a different correlation with every other asset. A bond has a certain correlation with a stock. One stock has a certain correlation with another stock (and a different correlation with a third). Stocks of one type (such as emerging market, high-tech or large-cap) are likely to be highly correlated with others within their category, but they may be either high or low in correlation with those in other categories. Bottom line: it’s hard to estimate the riskiness of a given asset, but many times harder to estimate its correlation with all the other assets in a portfolio, and thus the impact on performance of adding it to the portfolio. This is a real art.

Fixed income investors are directly exposed to another form of risk: interest rate risk. Higher interest rates mean lower bond prices – that relationship is absolute. The impact of changes in interest rates on asset classes other than fixed income is less direct and less obvious, but it also pervades the markets. Note that stocks usually go down when the Fed says the economy is performing strongly. Why? The thinking is that stronger economy = higher interest rates = more competition for stocks from bonds = lower stock valuations. Or it might be stronger economy = higher interest rates = reduced stimulus = weaker economy.

One of the reasons for increases in interest rates relates to purchasing power risk. Investors in securities (and especially long-term bonds) are exposed to the risk that if inflation rises, the amount they receive in the future will buy less than it could today. This causes investors to insist on higher interest rates and higher prospective returns to protect them against the loss of purchasing power. The result is lower prices.

Finally, I want to mention a new concept I hear about once in a while: upside risk. Forecasters are sometimes heard to say “the risk is on the upside.” At first this doesn’t seem to have much legitimacy, but it can be about the possibility that the economy may catch fire and do better than expected, earnings may come in above consensus, or the stock market may appreciate more than people think. Since these things are positives, there’s risk in being underexposed to them.

* * *

To move to the biggest of big pictures, I want to make a few over-arching comments about risk.

The first is that risk is counterintuitive.

The riskiest thing in the world is the widespread belief that there’s no risk.

Fear that the market is risky (and the prudent investor behavior that results) can render it quite safe.

As an asset declines in price, making people view it as riskier, it becomes less risky (all else being equal).

As an asset appreciates, causing people to think more highly of it, it becomes riskier.

Holding only “safe” assets of one type can render a portfolio under-diversified and make it vulnerable to a single shock.

Adding a few “risky” assets to a portfolio of safe assets can make it safer by increasing its diversification. Pointing this out was one of Professor William Sharpe’s great contributions.

The second is that risk aversion is the thing that keeps markets safe and sane.

When investors are risk-conscious, they will demand generous risk premiums to compensate them for bearing risk. Thus the risk/return line will have a steep slope (the unit increase in prospective return per unit increase in perceived risk will be large) and the market should reward risk-bearing as theory asserts.

But when people forget to be risk-conscious and fail to require compensation for bearing risk, they’ll make risky investments even if risk premiums are skimpy. The slope of the line will be gradual, and risk taking is likely to eventually be penalized, not rewarded.

When risk aversion is running high, investors will perform extensive due diligence, make conservative assumptions, apply skepticism and deny capital to risky schemes.

- But when risk tolerance is widespread instead, these things will fall by the wayside and deals will be done that set the scene for subsequent losses.

Simply put, risk is low when risk aversion and risk consciousness are high, and high when they’re low.

The third is that risk is often hidden and thus deceptive. Loss occurs when risk – the possibility of loss – collides with negative events. Thus the riskiness of an investment becomes apparent only when it is tested in a negative environment. It can be risky but not show losses as long as the environment remains salutary. The fact that an investment is susceptible to a serious negative development that will occur only infrequently – what I call “the improbable disaster” – can make it appear safer than it really is. Thus after several years of a benign environment, a risky investment can easily pass for safe. That’s why Warren Buffett famously said, “. . . you only find out who’s swimming naked when the tide goes out.”

Assembling a portfolio that incorporates risk control as well as the potential for gains is a great accomplishment. But it’s a hidden accomplishment most of the time, since risk only turns into loss occasionally . . . when the tide goes out.

The fourth is that risk is multi-faceted and hard to deal with. In this memo I’ve mentioned 24 different forms of risk: the risk of losing money, the risk of falling short, the risk of missing opportunities, FOMO risk, credit risk, illiquidity risk, concentration risk, leverage risk, funding risk, manager risk, over- diversification risk, risk associated with volatility, basis risk, model risk, black swan risk, career risk, headline risk, event risk, fundamental risk, valuation risk, correlation risk, interest rate risk, purchasing power risk, and upside risk. And I’m sure I’ve omitted some. Many times these risks are overlapping, contrasting and hard to manage simultaneously. For example:

Efforts to reduce the risk of losing money invariably increase the risk of missing out.

- Efforts to reduce fundamental risk by buying higher-quality assets often increase valuation risk, given that higher-quality assets often sell at elevated valuation metrics.

At bottom, it’s the inability to arrive at a single formula that simultaneously minimizes all the risks that makes investing the fascinating and challenging pursuit it is.

The fifth is that the task of managing risk shouldn’t be left to designated risk managers. I’m convinced outsiders to the fundamental investment process can’t know enough about the subject assets to make appropriate decisions regarding each one. All they can do is apply statistical models and norms. But those models may be the wrong ones for the underlying assets – or just plain faulty – and there’s little evidence that they add value. In particular, risk managers can try to estimate correlation and tell you how things will behave when combined in a portfolio. But they can fail to adequately anticipate the “fault lines” that run through portfolios. And anyway, as the old saying goes, “in times of crisis all correlations go to one” and everything collapses in unison.

“Value at Risk” was supposed to tell the banks how much they could lose on a very bad day. During the crisis, however, VaR was often shown to have understated the risk, since the assumptions hadn’t been harsh enough. Given the fact that risk managers are required at banks and de rigueur elsewhere, I think more money was spent on risk management in the early 2000s than in the rest of history combined . . . and yet we experienced the worst financial crisis in 80 years. Investors can calculate risk metrics like VaR and Sharpe ratios (we use them at Oaktree; they’re the best tools we have), but they shouldn’t put too much faith in them. The bottom line for me is that risk management should be the responsibility of every participant in the investment process, applying experience, judgment and knowledge of the underlying investments.

The sixth is that while risk should be dealt with constantly, investors are often tempted to do so only sporadically. Since risk only turns into loss when bad things happen, this can cause investors to apply risk control only when the future seems ominous. At other times they may opt to pile on risk in the expectation that good things lie ahead. But since we can’t predict the future, we never really know when risk control will be needed. Risk control is unnecessary in times when losses don’t occur, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong to have it. The best analogy is to fire insurance: do you consider it a mistake to have paid the premium in a year in which your house didn’t burn down?

Taken together these six observations convince me that Charlie Munger’s trenchant comment on investing in general – “It’s not supposed to be easy. Anyone who finds it easy is stupid.” – is profoundly applicable to risk management. Effective risk management requires deep insight and a deft touch. It has to be based on a superior understanding of the probability distributions that will govern future events. Those who would achieve it have to have a good sense for what the crucial moving parts are, what will influence them, what outcomes are possible, and how likely each one is. Following on with Charlie’s idea, thinking risk control is easy is perhaps the greatest trap in investing, since excessive confidence that they have risk under control can make investors do very risky things.

Thus the key prerequisites for risk control also include humility, lack of hubris, and knowing what you don’t know. No one ever got into trouble for confessing a lack of prescience, being highly risk- conscious, and even investing scared. Risk control may restrain results during a rebound from crisis conditions or extreme under-valuations, when those who take the most risk generally make the most money. But it will also extend an investment career and increase the likelihood of long-term success. That’s why Oaktree was built on the belief that risk control is “the most important thing.”

Lastly while dealing in generalities, I want to point out that whereas risk control is indispensable, risk avoidance isn’t an appropriate goal. The reason is simple: risk avoidance usually goes hand- in-hand with return avoidance. While you shouldn’t expect to make money just for bearing risk, you also shouldn’t expect to make money without bearing risk.

* * *

At present I consider risk control more important than usual. To put it briefly:

Today’s ultra-low interest rates have brought the prospective returns on money market instruments, Treasurys and high grade bonds to nearly zero.

This has caused money to flood into riskier assets in search of higher returns.

This, in turn, has caused some investors to drop their usual caution and engage in aggressive tactics.

And this, finally, has caused standards in the capital markets to deteriorate, making it easy for issuers to place risky securities and – consequently – hard for investors to buy safe ones.

Warren Buffett put it best, and I regularly return to his statement on the subject:

. . . the less prudence with which others conduct their affairs, the greater the prudence with which we should conduct our own affairs.

While investor behaviour hasn’t sunk to the depths seen just before the crisis (and, in my opinion, that contributed greatly to it), in many ways it has entered the zone of imprudence. To borrow a metaphor from Chuck Prince, Citigroup’s CEO from 2003 to 2007, anyone who’s totally unwilling to dance to today’s fast-paced music can find it challenging to put money to work.

It’s the job of investors to strike a proper balance between offense and defense, and between worrying about losing money and worrying about missing opportunity. Today I feel it’s important to pay more attention to loss prevention than to the pursuit of gain. For the last three years Oaktree’s mantra has been “move forward, but with caution.” At this time, in reiterating that mantra, I would increase the emphasis on those last three words: “but with caution.”