INSIGHTS

The Exceptional Economics of Hermès

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund own shares in Hermès International S.A. (RMS: ENXTPA), a leather good, luxury powerhouse best known for its infamous Birkin and Kelly Bags. Hermès is the epitome of luxury, offering premium goods such as bags for men and women, ready-to-wear garments, and accessories. Rising to prominence in the late 19th century as a saddlery manufacturer, Hermès has reigned supreme for six generations operating 315 exclusive stores and employing 15,000 artisans, who must each progress through a two-year training program before they are permitted to begin working with Hermès leathers. Performance over the last 10 years has been nothing short of exceptional and we believe that Hermès recent market de-rating provides investors in the Fund an attractive entry point to a business with exceptional margins, returns on capital and future prospects. To learn more, please read our Investment Summary Report by clicking the link below.

Warner Brothers Discovery ushers in a new era of “Content Kings”

Just some of the content the Warner Brothers Discovery (WBD) owns.

One of the recurring themes of the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund is IP (intellectual property). We love it. In our previous post, Content is King (and Undervalued) we wrote:

…the comparatively outsized impact legacy media has on popular culture and the zeitgeist (AT&T subsidiary HBO produced the show of last year, Succession; whilst ViacomCBS owned subsidiary Paramount produces arguably the second most important television show, Yellowstone; also consider the sheer amount of IP legacy media owns – everything from Mickey Mouse (Disney) to Star Trek (ViacomCBS) to The Wire (AT&T).

We love IP because it’s endlessly reusable; the value of Mickey Mouse is incalculable. The value of a library of content is also almost always underestimated – consider a movie like Ocean's Eleven. The 2001 Ocean’s Eleven reboot made US$450 million at the box office - but - like they say on the Shopping Network - “...and that’s not all”: the entire franchise has made US$1.4 billion at the box office (and even that’s not all – consider the streaming royalties ad perpetuum as a whole new generation discover the franchise years after it was produced). Warner Brothers Discovery, incidentally, owns the IP to Ocean’s Eleven and thousands of other movies, television shows, and related ephemera.

Children’s IP is even better. Consider Harry Potter. Harry Potter is one of the top grossing franchises of all time – grossing US$7.8 billion at the box office. Yet consider the new crop of children who are introduced to Harry Potter every seven years or so; that’s a whole new revenue stream. Or consider the limitless merchandising rights afforded by such valuable IP – the Wizarding World of Harry Potter (Orlando, Florida) is only the beginning. There’s trading cards, lollies, video games, clothing. You name it; someone has monetised it. In effect “evergreen” IP like this actually generates streams of recurring revenue, despite the initial investment often being made many years ago.

Our renewed focus on IP at present is because on Friday, 8 April 2022, the merger between Discovery Communications and the spun-off media unit of AT&T, Warner Brothers, took effect. We have owned fractional interests in both AT&T and Discovery in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund (“the Fund”) for this very reason – as of today investors in the Fund now own an interest in the new company: Warner Brothers Discovery.

This means investors in the Fund are now the proud owners of a global content behemoth. Warner Brothers Discovery (WBD) owns a lot of IP – from Ice Road Truckers to the hit TV series Succession to the DC Comics Franchise. It places WBD nearly on par with Disney, as illustrated in the graphic below:

We referenced in “Content is King (and Undervalued)” how consolidation is the likely, and perhaps inevitable outcome for studios. The cost of creating content simply keeps scaling, and to compete effectively (with pricing power) one’s studio needs to be a colossus. The resulting company is just this - WBD becomes a powerhouse of content (especially in terms of library) that can compete in today’s incredibly competitive media landscape. Investors in the Fund also own fractional interests in Paramount and Disney; if we were to own each company “whole” this would represent a ~51% interest in the total annual content consumed in the US alone.

The challenge now for WBD is to enhance its streaming platform to compete with that of Disney+ and Netflix (this is also the challenge which Paramount faces). The challenge is highlighted in the chart below – which details the demand shares for streaming catalogs – here WBD sits in third place; which illustrates just how effectively Netflix and Hulu (owned by Disney and NBC) have rolled out their platforms.

Despite its scale, Netflix is still at a disadvantage – early in its transition to a streaming platform it licensed shows from studios (Warner and Discovery among them) when the studios did not realise the value of their catalogs. Now the studios do, and they are pulling their content from Netflix as their license agreements expire; Netflix is disadvantaged in an “arms race” for content, unlike studios with a large library of valuable IP. Without a doubt there is an “arms race” for content — WBD is set to outpace Netflix’s content spend in aggregate, coming in second to only Disney. The difference between Netflix and WBD is IP — WBD has a vast library of hundreds of thousands of hours of content and incredibly strong franchises. Netflix is still building their IP library — it is an uphill battle in our view.

Source: Purely Streamonomics

Whilst there is an “arms race” between every major studio, the real challenge for WBD is to leverage their immense content library and render it to a streaming platform which provides access to all of WBD’s stellar content. The goal is conversion of audiences to an on-demand platform. We can’t help but feel WBD has been dealt a “royal flush” — with content from the likes of HBO, Discovery and the DC Franchise WBD has a veritable goldmine of IP — and content remains King. We are watching how CEO David Zaslav steers this incredibly exciting new company – and we can’t wait to see the new season of Succession (an HBO production, as it happens).

The Insatiability of Inflation.

One of the metrics we look at when we acquire a fractional interest in a company is its Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). Think of it as what management actually returns on the capital employed in a business – a company that consistently returns +15% on capital employed is going to be a very attractive business in the long run. For instance, Hermes returns +16% on capital employed - this is part of why we acquired shares in Hermes for the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund portfolio, combined with heavily aligned management – the Dumas family owns over 50% of the company, and an unassailable product – if you want to beat inflation, just buy a Birkin! — see chart below.

Source: Baghunter

Inflation’s insatiability, is the subject of the post. As of February 2022, inflation in the US is estimated to be ~7.9%, whilst in France it sits at ~4.5%. In New Zealand, inflation currently sits at ~5.9% (as of March 2022). In fact, all current estimates now peg global inflation to be higher – you don’t need to be an economist to notice just how expensive the costs of basic goods at the supermarket have become in the past year.

No business owner is a fan of inflation. We think of ourselves as business owners, with fractional interests in a variety of businesses. The problem is that inflation eats away at “actual” returns. Warren Buffett calls this a “Misery Index”. For instance, Hermes earns a return on invested capital of +16%. This is wonderful and should be lauded; we wish all businesses could do this. Yet factor in inflation, and the “real return” becomes ~11.5% (it’s even worse if you use US inflation as your yardstick – it reduces what was once a great return to a pallid ~8.1%). In an inflationary environment, even the best businesses look merely good and good businesses look mediocre — and as for average businesses – well – they’re effectively returning nil.

In an inflationary environment the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) by even the best business becomes poor. Consider the average ROIC for the S&P 500 – it sits around ~9%. Factor in inflation, taxes and other costs associated with transferring earnings to the owner’s pocket and the ROIC is practically zero today.

We do not have a solution to this. Central Banks around the world appear to be reducing their balance sheets, raising interest rates, and taking steps to curb inflation’s insatiable rise. In the meantime, it appears to us that the only solution is to own companies which earn substantially higher returns on capital than their peers and the market at large.

As a thought experiment, let’s take a few of “our” companies, and compare them with their “real” return (ROIC minus inflation): Meta: +20.9%, Estee Lauder: +9.3%, Visa; +7.9%, Autodesk: +6.3%. In non-inflationary environments, of course, these companies generally all have double digit returns on invested capital. Double digit returns act as a growth engine in non-inflationary environments (to paraphrase Charlie Munger: after 20 years, with a double digit ROIC, you’re going to end up with a hell of a result). In inflationary environments they act as a cushion against the perils of a rapidly devaluing money supply. In our view, owning companies which produce an above-average return on invested capital is the only rational insurance on your own capital in an inflationary environment.

Accordingly, in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund, we are focused more than ever on acquiring fractional interests in companies which generate an above-average return on invested capital; acquiring them at an attractive price, and letting the businesses do the rest.

Introducing Universal Music Group

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund own a share of Universal Music Group N.V. (UMG), the world’s largest record company, with +32% of the world’s total music revenues. There are few things surer than the predilection of humanity for music. It is the shorthand of emotion, as Tolstoy once quipped. To own UMG is to earn a “royalty” on people listening to music, something we are certain is bound to continue til the end of time. As streamers such as Spotify have matured, music industry revenues have recovered to near-early 2000s levels and a symbiotic relationship has developed between streaming platforms and record companies that is mutually beneficial (investors in the Global Shares Fund own both sides of the transaction via our investment in Spotify). The crown jewel in UMG’s crown is its extensive catalogue of music, ranging from Bob Dylan to Sting to “ol’ blue eyes” himself, Frank Sinatra. We believe UMG, with its rich catalogue, is well positioned to continue earning a royalty on one of humanity’s timeless pleasures -- music.

How do wars and crises affect equities? Some counterintuitive data.

There is little point in beating around the bush. Stock markets have been subject to heightened volatility. The short-term results aren’t pretty. Even “value”-orientated portfolios have been subject to “market forces”.We are constrained by our mandate – we cannot short (and would not want to anyway) or engage in derivatives. This is most likely a good thing if history is any guide – the investor who invested their portfolio into US equities on the eve of WWI would’ve seen their portfolio rise, on average, ~47% between 1914 and and 1923. A similar scenario occurred during WWII – UK equities outperformed gold from 1939-1948. In other words: hedging and derivatives might window-dress returns in the short-term but in the long-term a diversified equities portfolio delivers a more than satisfactory return.

The volatility is due to Ukraine. As of writing Putin has engaged in a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The US and its NATO allies have responded by imposing sanctions on Russian banks, and have restricted Russia’s sovereign debt and trade apparatus. Germany halted the pipeline Russia was building to transport natural gas; to which former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev tweeted “welcome to the new world of expensive natural gas, Europe!”

Biden’s sanctions are typical of the US. They cause the greatest harm to Europe (the US has ample natural gas pipelines). They aren’t an incentive for Putin to cease invading Ukraine – the harm caused by cutting off Russia’s vast natural resources has a greater effect on the rest of the world.

The good news is – history suggests that holding (and adding to) equities during a war still results in outperformance against all other asset classes.

We do not know what the future holds but we can look to history for what markets do in times of crisis. For instance, if you were to invest in the Dow Jones at the start of WWI (1914) and hold until the end of the war (1918), your compounded returns would’ve been about +8.7% per annum; or +43% total return.

If you were to do the same with US equities in WWII, your compounded return would have been +7%. If you held UK equities rather than gold in WWII (the equities of a nation crippled by WWII) you would’ve handily outperformed gold, a traditional safe-haven asset.

We recently read David Lough’s “No More Champagne: Churchill and his Money” (spoiler alert: Churchill was a world-class statesman and a world-class spender). Churchill flitted around with equities in WWI and at the outbreak of WWII; he was always looking for the “next big thing” and selling his previous holdings - often at a loss. If only Churchill had simply held a basket of equities for the duration of either war!

What about conflicts of more recent times? During the Korean War (1950-53) the Dow delivered an astonishing +16% return annualised, whilst during the Vietnam War (a prolonged, messy and expensive conflict if there ever was) the Dow delivered a return of +5% annualised. Two months after 9/11 the stock market returned to pre-9/11 levels.

The commonality throughout all these conflicts and wars is that volatility was priced-in early on. The anticipation of conflict caused a sharp drop in market indices, whilst the first month or two of said conflict led to panic selling as market participants adjusted to new information, as illustrated in the chart below:

Source: AMP Capital

A few interesting points to be made, then. The first is that the more serious and involved the war the longer the market takes to resolve itself - but it does resolve. In a diplomatic crisis (i.e. Cuba) the market resolves itself hastily. Even the Iraq war – an event over which an endless quantity of ink has been spilt - resolved itself with comparative speed in the eyes of the US equities markets.

S&P 500 and associated wars and crises

Source: Investmentoffice.com

Another compelling case for investment in equities (in other words, assets that earn capital in very real terms) comes from examining the S&P 500 since during several major wars and crises. The index has steadily maintained its upward incline in the face of wars and crises. This is no secret. The benefits of indexes or being fully invested in equities have become dogma - it is clear for all to see - yet it is remarkable how this wisdom is forgotten in times of war and crisis.

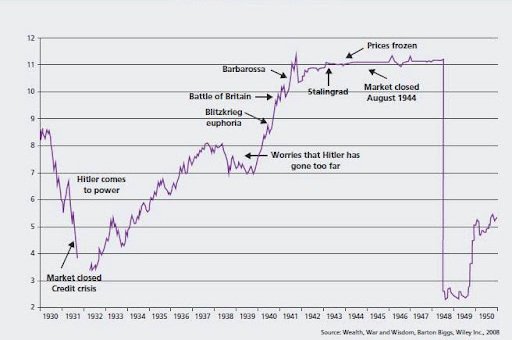

Charlie Munger likes to say “invert, always invert” - so it’s interesting to look at the flipside of WWII, from the perspective of not the US or UK equity markets but those of the eventual loser of the war – Germany. How did they fare?

German CDAX Index: 1930 - 1950

Source: Wealth, War and Wisdom (Barton Biggs)

The results are interesting – the German CDAX (an index of all stocks listed on the Frankfurt stock exchange) reacted very much the same to WWII as the Allied powers did. It suggests that market participants in a war react the same to material news regardless of which “side” they are on: all is fair in love and war. The other remarkable thing is that post-WWII German stocks recovered relatively quickly - by 1950 German equities were unscathed by one of the most terrible wars in history.

German CDAX Index: 1840 - 2010

Source: CDAX

Of course, nobody knows the future. Yet what is clear from the current Russia-Ukraine conflict (and the accompanying response from the US, the Eurosphere and Anglosphere) is that a high amount of volatility has already been priced in. If history is any teacher, high quality equities (real companies which generate actual earnings) remain the best way to take part in the economic success story of the world.

Universal Music Group — Music is Universal

There are few things surer than the predilection of humanity for music. It is the shorthand of emotion, as Tolstoy once quipped. All societies throughout history have developed their own musical language; whether it stemmed from the lyre (ancient Greece), the lute (medieval Europe) or the well-tempered clavier (an absolute game-changer that gave birth to the modern piano and in a way, all music that came after it). Warren Buffett’s case for investing in Gillette was famously simple: most men shave, and most men will continue to shave ‘til day dot. Our thesis on UMG is similarly simple: Music is Universal.

Universal Music Group (UMG) is one of the “big three” music publishing companies (the other two are Warner Music and Sony). Like its brethren it is the result of decades of industry consolidation and hence it is a diverse collection of assets which management has pieced together into a coherent whole (whilst UMG’s origins stretch back to Decca Records, in 1934, its various assets has, at points, been owned by Panasonic and prior to that Seagrams, the distiller). UMG now holds a 32.1% market share globally, which makes it the largest in the industry. It also is the only publisher to have consistently grown its revenues from 2018-2021, largely due to its embrace of streaming and modern mediums of music consumption (Spotify and the other streamers, TikTok, music licensing on memes and so on).

We like industries which have been subject to consolidation, especially ones that are progressing towards an oligopolistic structure. Industries at their birth are often dense with competition. In 1896, when the bicycle became popular there were 140 publicly listed companies engaged in the manufacture of bicycles; by 1901, 40 of those had gone bankrupt and over the next ten years another 60 had gone out of business. The invention of the bicycle was a significant advance in technology (in some ways, it was the most egalitarian advance in technology since the printing press – no fuel needed and relatively cheap and accessible). Yet a significant new technology is no guarantee of a successful business. The more businesses engaged in a new technology, the more competition, and the less chance the business will produce what we are all interested in at the end of the day – significant cash flows.

The catalyst for the recorded music industry were the twin inventions of the radio and recorded sound (first on wax cylinders which quickly evolved to vinyl discs). The two were bound together tightly; recorded sound allowed for the first time in history for music to exist outside of the present. Radio allowed for the effective “streaming” of it in a way which allowed almost unlimited distribution. The fortunes of the two industries were, for a time, linked at the hip. There were numerous recorded music companies and numerous radio companies. Both industries consolidated; for instance CBS transitioned from a radio station operator to a TV company, as did NBC. Decca (the historical precursor to UMG) merged with Universal-International and later MCA. Now the music industry has consolidated further resulting in the “Big 3” and the other side of the transaction – now streamers, not radio – are consolidating, too. There are therefore two catalysts that inform our view of UMG: the wider consolidation that has largely resulted in oligopolistic market share, and the virtuous nature of the other side of the transaction - streamers - and industry consolidation continuing amongst these players.

A virtuous cycle

There are two sides to a music transaction; the ownership of it and the distribution. The ownership of the song/track by the record company (often in tandem with the musician’s own company) is broken into two parts - the “master” rights and the “publishing” rights. The record owner of the rights receives royalties in three ways: mechanical royalties (.ie. the reproduction of the work; this is where revenue from streamers occurs), public performance royalties and synchronisation license fees (i.e. when a work is used in any derivative fashion; think of the sample in Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby” which is taken from Queen’s “Under Pressure” - every time “Ice Ice Baby” is played, the owner’s of “Under Pressure” get a royalty too).

Streamers, like Spotify, which investors in the Elevation Global Shares Fund own a share of, receive revenue from their subscribers; in turn Spotify pays a proportionate royalty to the rights owner; often this is UMG. This is counted as a ‘mechanical royalty’. Other popular apps - like TikTok - pay a performance royalty when users make content which uses a song.

We quite deliberately own both ends of the transaction. Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund own UMG via a direct holding, but also through our ownership of Tencent (the Chinese technology stalwart that owns 20% of UMG) and Prosus (a South African holding company which owns 28.9% of Tencent, and Vivendi, which spun-off UMG in 2021 and continues to hold a 10% stake). We also own Spotify (and we published research on it in April 2020 and an update in July 2020).

Why do we own both sides of the transaction?

The reason is quite simple. The two are correlated; the more people who stream music, the more royalties UMG will receive.

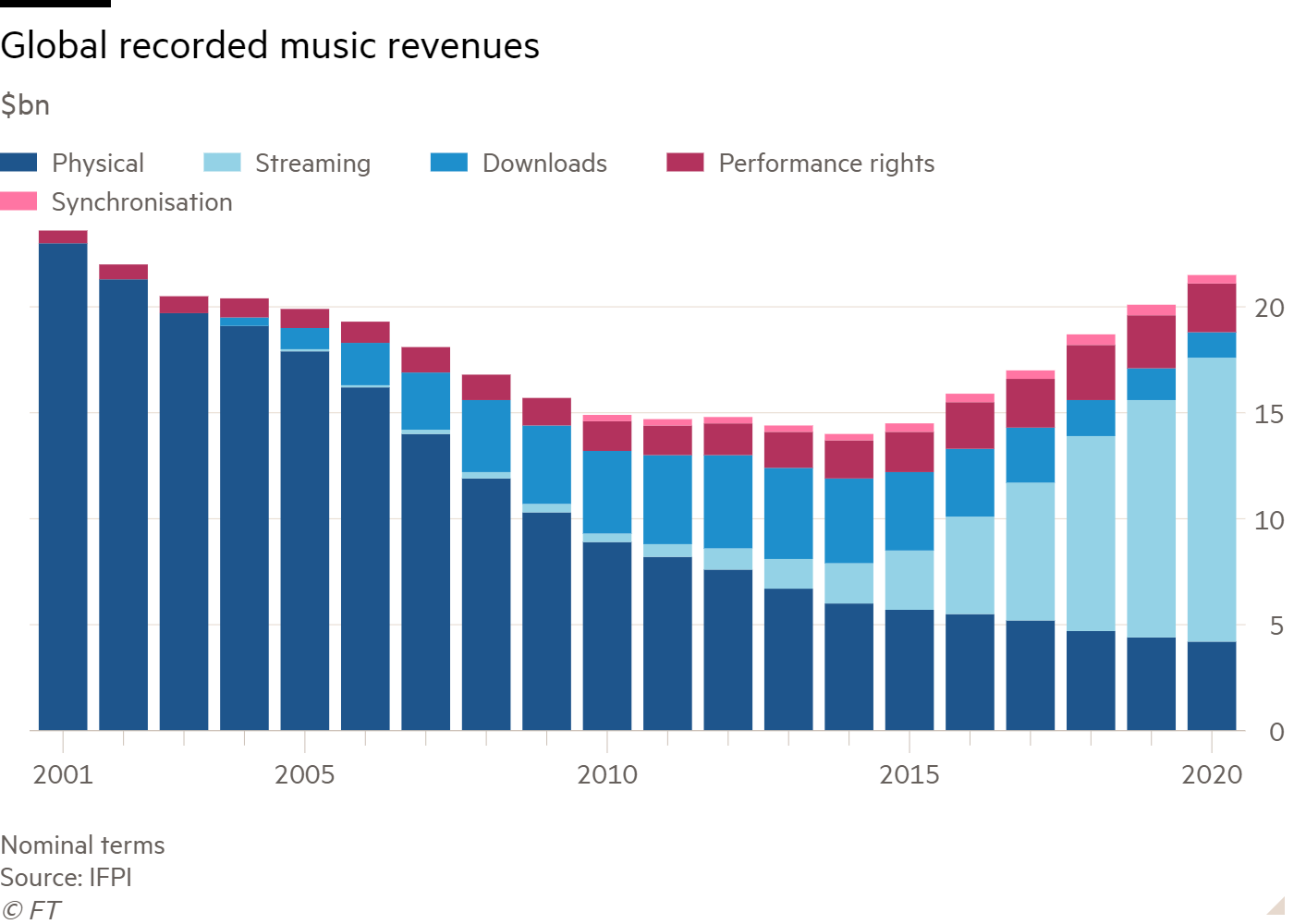

Source: Financial Times

The music industry has gone through two major disruptions in the last twenty years. The first is the “death” of the physical format - the CD - and the ascent of downloaded music. The second was the “death” of downloaded music and the ascent of streaming. Something happened between the 2000s and years following; total revenues declined, hitting their nadir in 2014. It’s important to understand what happened to understand what occurred next: in effect, the record companies didn’t know how to pivot towards a new digital era. Pirating of music was rife but also downloading music is a laborious process compared to a streamer, where millions of songs sit at your fingertips. The industry had continued to pour the bulk of its efforts towards the physical format (CD’s), which was a dying format – the iPod had seen to that. Secondly, the music industry couldn’t quite profit from downloads enough. The frequency wasn’t great enough.

Streaming changed this. Music industry revenues have now recovered to their early 2000s heyday directly proportional to the number of users on the various streaming platforms – Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, YouTube Music, Amazon Music, etc. The secret is the increase in frequency – whilst streams pay mere fractions of a cent per song play to the record company, the frequency is much greater. This bears many similarities to the co-dependent relationship of recorded music and radio which occurred at the advent of the medium. In other words, it’s full circle: streaming is radio, and the two are highly correlated.

Well positioned

We aim to not make hyperbolic statements and claim something is the “greatest” in its field. Leica is undoubtedly a great camera brand yet the best selling “camera” is the smartphone. As we have mentioned previously, the recorded music industry has a “Big 3” which all benefit from the same base advantages. UMG has the same advantages that both Sony Music and Warner Music have. However, UMG is slightly unique. The first is that it still retains a meaningful stake in Spotify (~3.4%). Sony Music has reduced its holding in Spotify to ~2.0% and Warner Music sold its stake entirely. UMG also owns ~1.0% of China’s most popular streaming service - Tencent Music. It is clearly in UMG’s best interest for streaming to succeed; as streaming’s fortune rises, so do those of UMG, and vice versa. It also means UMG has “skin in the game”; contrast this to that of the comparatively distanced approach record companies had to downloaded music in the first iteration of non-physical music.

The other quality that distinguishes UMG from its competitors is a technology-led commitment to the future. The company moved its headquarters from New York to LA, in a bid to be closer to the heart of the technology sector, as well as engaged proactively in agreements with next-generation services that use its content, like TikTok. It is easy for this to come across as corporate double-speak yet mediums like TikTok are more than hype; performance royalties have become a meaningful aspect of music industry royalties.

Finally, there is the most obvious aspect of size. UMG is the largest record company by far. UMG has used this advantage of scale to negotiate favorable agreements with partners such as Spotify, YouTube and TikTok. Their pricing power is obvious – platforms which do not have UMG’s content are missing out on perhaps a third of all recorded music. To once again quote Sumner Redstone: Content is King.

Introducing Ubisoft

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund own a share of Ubisoft (UBI.EPA), a powerhouse developer renowned for creating the expansive worlds found in videogames such as Assassin’s Creed, Far Cry and Watch Dogs. Ubisoft produces, publishes and distributes video games for consoles, PC, smartphones and tablets in both physical and digital format. Headquartered in Montreuil, France; it is one of the top four independent publishers globally with a 9.2% share of physical sales in the US and 9.0% share in Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA). While the stock has lagged behind its peers in recent time, we believe the advances in shifting to recurring revenues and the pipeline of exciting releases means Ubisoft is primed for an improved performance in the medium-term.

The Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund first acquired Ubisoft shares in August 2021. Ubisoft, as at 31 December 2021, currently trades at a discount of 38.54% to 128.67% to our estimates of Ubisoft’s intrinsic value, making it another attractive value investment in the Fund’s portfolio.

Content is King (and Undervalued)

Source: Lightshed Partners

“Content is where I expect much of the real money will be made on the Internet, just as it was in broadcasting.” - Bill Gates, 1996

Last week we included in our Sunday Reading Newsletter the above chart from Lightshed Partners, which illustrated just how much smaller the media giants of the past are compared to big tech. It’s as if Goliath went up against a tea lady. ViacomCBS is so small on the chart that you could be forgiven for mistaking it as a pixel on your screen – whilst Lionsgate is barely visible at all.

Consider for a second just how remarkable this is. In the 50s and 60s CBS was a giant among corporations – CEO Bill Paley had transformed a former radio station into a powerhouse; in 1961 CBS was the 16th largest listed US company by revenue. Even more extraordinary is AT&T - which in 1961 was the 10th largest corporation by revenue, yet is all but dwarfed by a handful of firms which were decades away from existing in the 60s (this is made all the more remarkable consider that, as of writing, AT&T still includes media assets like Warner Media and CNBC – so AT&T is dwarfed by big tech despite having two streams of revenue – telecommunications and media).

There is good reason for the size of big tech. Others have written eloquently about it; yet in this market where pundits now talk breathlessly of pivoting to so-called “cyclicals” and “tech stock sell-off” it’s perhaps worth remembering that these companies generate enormous amounts of cash (Apple’s net profit after tax last year was c.$US94 billion, whilst Microsoft’s was c.$US67 billion*). We can think of few credible alternatives to Google (Alphabet), or to Instagram (Facebook/Meta), or to the comprehensive suite of products Microsoft offers. These companies are proverbial cash generating machines.

Consider, then, the relatively small size of legacy media. Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund currently own shares in a number of legacy media companies: AT&T, AMC Networks, Comcast, Discovery Communications, Disney and ViacomCBS.

AT&T is currently spinning off its media assets and merging them with Discovery to create WarnerDiscovery. In December 2019, Viacom merged back with CBS after a 13 year separation (the original incarnation of Viacom included CBS, but in 2006 the two companies split into two). In our view further mergers and acquisitions will ensue.

Why?

Simply put, more people are watching original content on a screen than ever before. This is evident by ever-growing subscriber numbers to streaming services, detailed in the chart below from AdWeek. The content is being watched by a lot of people as the basic tenets that drive humans has not changed: as Bill Gates wrote in 1996 paraphrasing Sumner Redstone from 1974 in Magazine Editing and Production, and from where the title of this blog post derives: “Content is King”. Gates proposed that the winners of the internet will be those who create the best content. He then proposed what is still the basic structure for making money from content on the internet: either via subscription or advertising.

What Gates prophesied has come to pass; “anyone with an internet modem” can create content and they have; the success of TikTok, YouTube and Instagram is due to user-generated content. The value of content applies on a larger scale, too: as streaming has become commonplace the money spent on content has increased dramatically. Global content spending in 2021 was +US$220 billion (+14% YoY); this is consummate with the number of subscribers to the various streaming platforms (which have all increased in the last year). Demand for content drives spend. Partially the extraordinary spend on content by media (legacy and otherwise) can be explained by a shift in monetisation strategies: legacy media can benefit directly from SaaS-like recurring revenues in the form of streaming subscriptions which generates substantial cash flow at scale.

Consider, then, the relative size of big tech to legacy media and the comparatively outsized impact legacy media has on popular culture and the zeitgeist (AT&T subsidiary HBO produced the show of last year, Succession; whilst ViacomCBS owned subsidiary Paramount produces arguably the second most important television show, Yellowstone; also consider the sheer amount of IP legacy media owns – everything from Mickey Mouse (Disney) to Star Trek (ViacomCBS) to The Wire (AT&T). We have previously talked extensively about the lasting and often under-appreciated value of a library; an example of this outside of media is our 2015 presentation on a previous investment, Adidas, which can be viewed here.

Today, we hypothesise that the highly valuable content libraries legacy media owns alongside the growing demand for content renders legacy media a very attractive acquisition or merger target; Content remains King.

The value of content libraries and IP is significant. A new platform may have very deep pockets (Apple TV) yet without a library and IP the endeavour is fraught with risk: the marked failure of ex-Disney, ex-Dreamworks executive Jeffery Katzenberg’s Quibi is testament to that. A cheaper and more tenable solution to building a content library may be to purchase a legacy operation. The resulting company from AT&T and Discovery’s spinoff/merger, WarnerDiscovery, will have a value of c.US$100 billion. This is a mere fraction of Amazon’s market capitalisation (US$1.64 trillion) or Apple’s (US$3 trillion). Owners of these companies are well aware of the size disconnect between deep-pocketed tech and the size of their own company: they are small fish in the face of a proverbial whale; and they have structured accordingly – John Malone is giving up his supervoting-class shares in Discovery to effect the WarnerDiscovery merger and, in our view, render a potential acquisition/merger of WarnerDiscovery more palatable in the future**.

The bottom line is: Content is King; legacy media is dwarfed by big tech; to big tech, content is cheap - Game On!

*Source: Capital IQ

**”Malone agreed to turn in those shares for common equity because he wanted to give a combined WarnerDiscovery flexibility to sell itself in the future -- most likely to a deep-pocketed technology company like Amazon or Apple or another media behemoth like Disney, according to a person familiar with the matter.” Source: CNBC

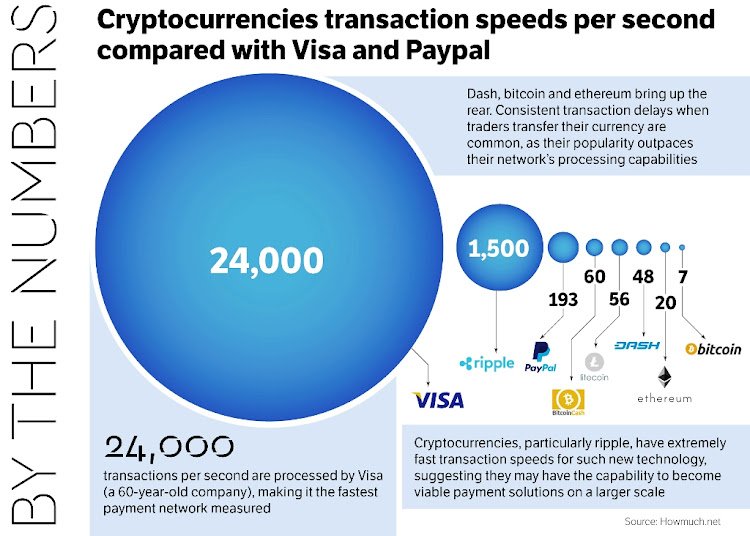

Visa, Mastercard, and the blockchain

Source: Howmuch.net

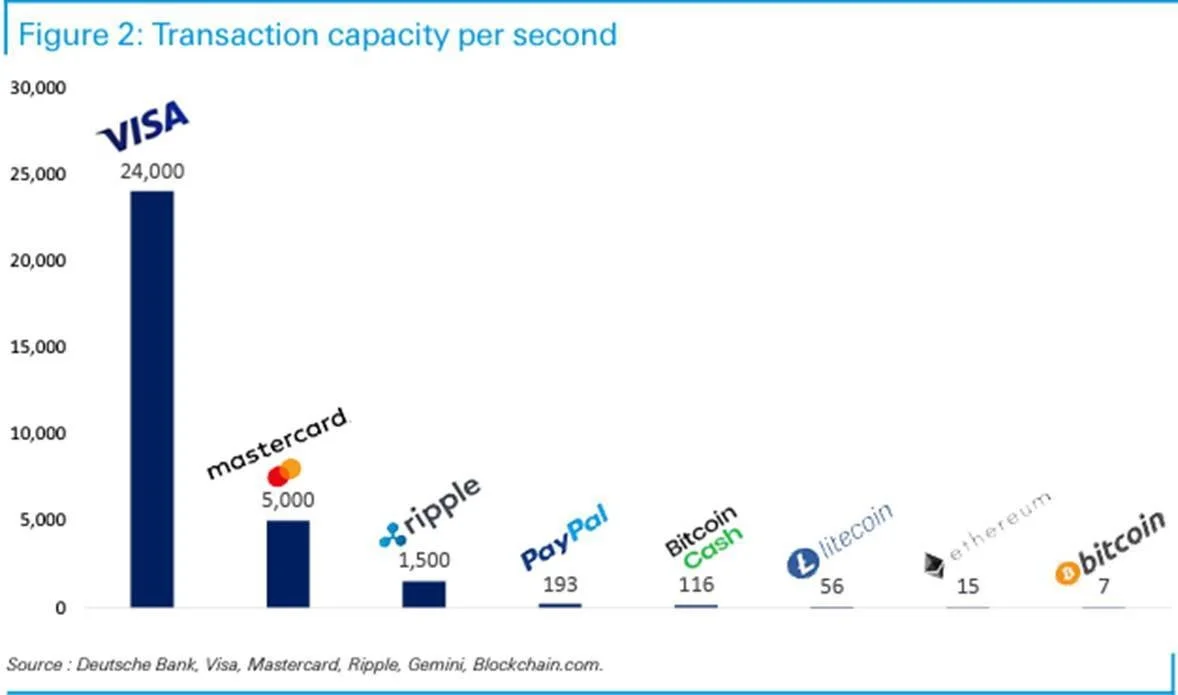

We had a few erudite replies to our recent blog post on Visa and Mastercard, a number of them which concerned blockchain and Bitcoin; we thought it might be constructive to further detail why Visa and Mastercard’s transaction processing speed (TPS) is by order of magnitudes faster than anything on the blockchain currently, and why we see this as a significant competitive advantage for the foreseeable future.

Blockchain, of course, is the overarching protocol which is used by cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. If Bitcoin is a currency, then blockchain is the infrastructure which allows it to flow from place to place. It is the obvious direct competitor to Visa and Mastercard’s own infrastructure. Traditional payment infrastructure requires a third party to verify the transaction (Visa, Mastercard and so on). Blockchain verifies transactions in a decentralised manner, via multiple miners who then complete “proof of work” to verify the transaction. This burden of “proof” is spread across many thousands of miners, hence the decentralisation.

Blockchain is an attractive protocol and proposition as a “source of truth” for documentation which has typically been hampered by bureaucracy. An example might be property records and the transfer of them, which are typically routed through government departments and are reliant on protocol and processes which are often slow and inefficient. Yet blockchain’s transaction speed still pales in comparison to Visa and Mastercard’s own networks -- the most well known cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, can process about 7 transactions per second. Visa’s network can process up to 24,000 per second. Other cryptocurrencies can process more transactions per second: Ripple can handle up to 1500, though the vast majority process in the low double digits (Ethereum can process up to 25 per second). The relative difference in processing speed is due to scalability. Real estate transactions occur less frequently than everyday transactions, so the issue isn’t a problem for blockchain to handle. Yet in the context of transaction processing for everyday payments the problem of blockchain’s scalability is significant. Visa and Mastercard can process more transactions by an order of magnitude.

The scalability problem

The scalability of Bitcoin and most other cryptocurrencies is related to block size. On average, a new block is mined every ten minutes by Bitcoin miners, which averages at about 4.6 transactions per second. With bitcoin, the two variables which dictate transaction speed (TPS) are block generation time and block size. Block size is currently hard coded at 1MB, while block generation time can be reduced by reducing the complexity of the hashing puzzle used to create new “blocks”. In other words, there are two levers: size and complexity. This is often referred to as “the blockchain trilemma”.

On average Visa processes +1,700 TPS. To achieve that average TPS in bitcoin, the entire system would would need to be scaled by 377x. This could be achieved either by increasing the block size to 377 MB (remember, it’s only one MB right now) or increasing the block generation time to 1.5 seconds (the average is 10 minutes), or by a combination of the two. The challenge is significant. There are possible solutions to the scalability problem; parallel proof of work (ie. engaging in the same “proof of work” from multiple miners) or incorporating multiple transactions into the same batch (which reduces the size of the total transactions by about 5.5x). “Batching” transactions is efficient, yet Bitcoin limits this -- transactions from multiple wallets cannot be batched.

This is partially why we believe that Visa and Mastercard’s dominance of global payments and transactions will continue: the scalability problems of blockchain are significant. Visa and Mastercard’s TPS is lightyears faster than anything currently offered by the blockchain, which should stand up as a durable competitive advantage in the business Visa and Mastercard dominate - everyday payments - for many years to come.

Sources cited:

Diana Chen -- Understanding the Scalability Issue of Blockchain

How we think about Roblox

Roblox was brought to our attention by the small humans in our life - nieces and nephews and children of friends (one of whom said a Roblox gift card is her emergency present if her children are going to a party and she hasn’t got anything). As a wry commentator put, never underestimate a child and their parent’s credit card.

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund have made a +73.46% return on Roblox as of writing (we first acquired Roblox shares about seven months ago). We like to investigate companies we invest in thoroughly - this included both playing Roblox, reading about it, watching videos on YouTube of others playing it (there are many, and their popularity is astounding) and ultimately trying to discern where the value of the company lies.

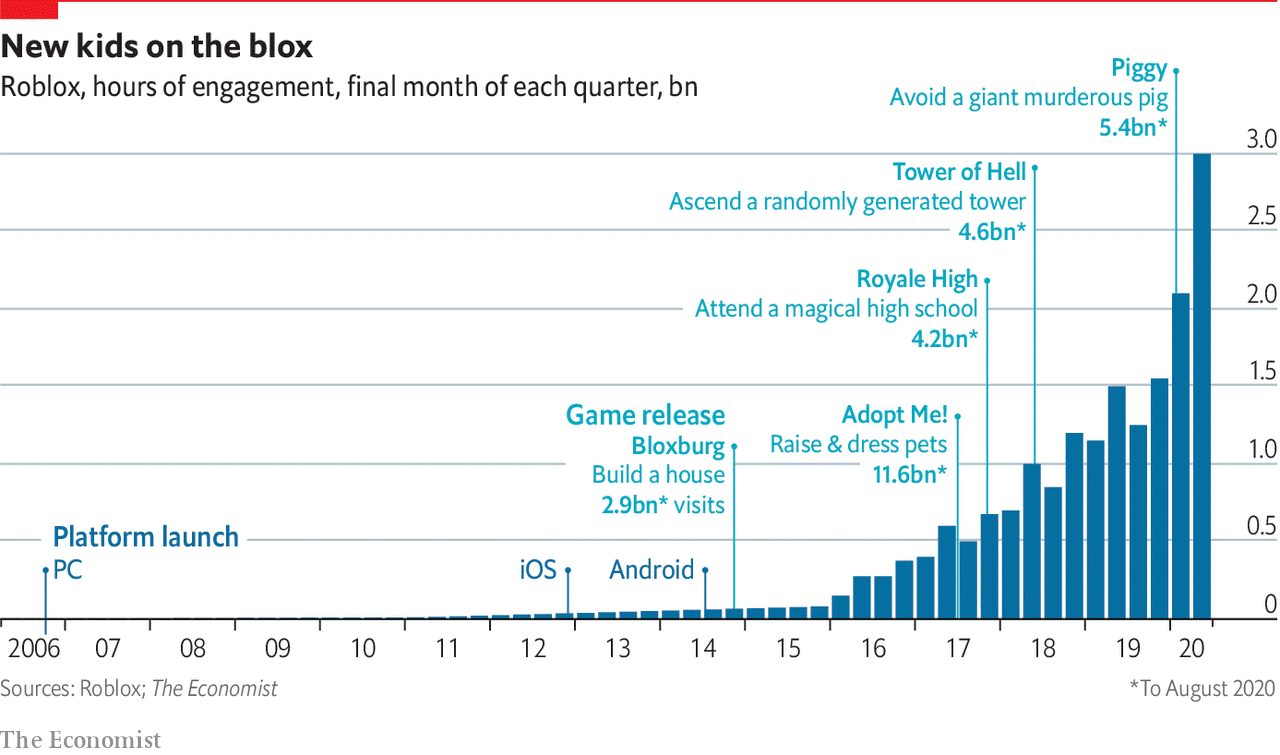

The most important point to understand about Roblox is that it’s not a game. It is a platform. In this sense Roblox hovers somewhere between the open-world building of Minecraft, the broadness of Meta’s platforms and the hardware-centric basis of “old school” platforms like Sony’s Playstation. Roblox has elements of all of those, yet it stands unique against them. Roblox is a platform which allows for the building of experiences and games and worlds. It is incredibly -- almost mind boggingly popular -- it has 43 million daily active users; +7 million developers and users have engaged with it for 11.2 billion hours in the past three months alone. What drives this growth? Developers, and users responding to it. New games and experiences created in-platform have led to “inflection” points which have a direct correlation to the growth of the platform.

The extraordinary thing about Roblox is that all those infection points are generated by developers. Developers themselves are largely made up of Roblox’s vast userbase. There appears to be a “funnel” from user to developer. A user might enter the Roblox system at a young age (13 years old or younger) and “graduate” to a developer. New content is developed in the thousands every day by the +7 million developers developed through Roblox’s “funnel”. The effect is like a flywheel which gets faster and faster -- more users creates in turn more developers which creates in turn more content, which leads to more users (and so on).

We think of Roblox like an “open garden”. Traditional software development often utilises a “closed garden” framework -- users are kept within the walls of the platform, whether it’s Apple’s or that of Sony’s Playstation. Robolox is radically open -- there is no barrier for a user to become a developer, or be a user-developer hybrid. Roblox has created a “metaverse” over the past decade which is built to support the ever-increasing demand of an “open garden”. In essence, Roblox has more in common with the outside world than it has with other “walled garden” platforms.

The Walled Garden Problem

Walled gardens offer a degree of control over the platform’s environment; for instance, Playstation developers must be vetted by Sony; developers of Apple apps are limited by Apple’s own guidelines and approval process. The limitations continue to pile up for platforms which deal with a 3D environment -- a Playstation game often requires a multi-million dollar budget and a team of developers; a Roblox game or experience could be developed by a 13 year old. The open garden is one possible solution, the success of which has been demonstrated by Roblox.

Incentivising Developers

“Never, ever, think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives.” - Charlie Munger

Roblox’s growth is powered by its developers. Charlie Munger notes the incredibly strong power of incentives is a key (if not the key) driver in human behaviour. Roblox pays developers 70% of the in-game currency (Robux) spent within their experiences, and 30% for items that are sold by developers in the Avatar Marketplace. Developers are highly incentivised to create more experiences. This is a tangible way to monetise popularity directly (TikTok and other platforms monetise popularity, but indirectly, via sponsorships and ads and the like). The power of incentivisation is precisely why we are confident in Roblox’s ability to grow and scale.

Bookings

Roblox’s management measures revenue via bookings - the amount of Robux bought in-game. Due to GAAP it is treated as deferred revenue, yet for all intents and purposes it is revenue -- users buy Robux to spend. The gap between revenue and bookings is significant -- third quarter bookings were US$637 million -- reported revenue was US$509 million (a 21% gap). Hence when we think about future earnings, we think about Roblox’s bookings. Their bookings have grown at +120% YoY. The flywheel is mighty efficient.

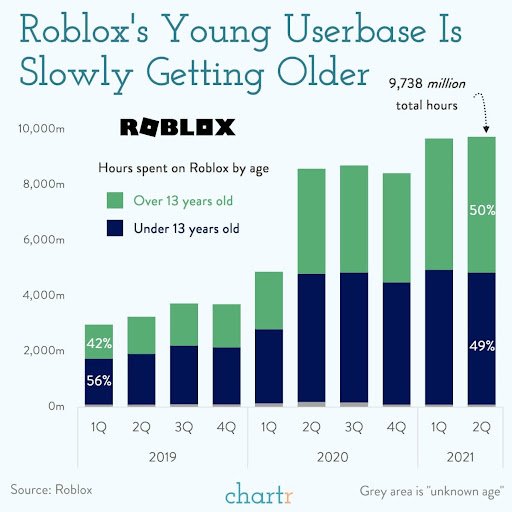

The Age Question

As of Q3 2021, 50% of Roblox users are aged 13 and over -- the first time in Roblox’s history. We think this represents significant in-roads to an older demographic. A common refrain we hear is “isn’t Roblox for kids?” yet it’s clear as the Roblox platform evolves the platform can (and is) appealing to a broader demographic of users.

The Metaverse

We would be remiss to not discuss the obvious. Meta (formerly Facebook)’s Mark Zuckerberg has invested +US$10 billion in the metaverse -- scant few had heard of the metaverse a decade ago. Roblox has been building its own metaverse platform for over a decade. It has a decade’s head start against the competitors. We often talk about the myth of the first mover -- the first mover is rarely the most successful business (Google was not the first to search, after all --nor was Walmart the first entrant to the discount store). Roblox is not the first entrant to the metaverse, either -- SecondLife and MMORPGs come before it and a host more. Yet Roblox has achieved a system which is both more refined, more scaled and more compulsively enjoyable than its predecessors. The “meta” element of the platform has scaled appropriately - . Roblox has a partnership with Sony music which has led to Sony’s roster of artists having launch events live in-Roblox. Gucci opened a “Gucci Garden” on Roblox on May 17th. Netflix has recently incorporated elements of the hit TV show “Squid Game” into Roblox. The metaverse can be whatever you want it to be -- Roblox has a platform which already has +7 million developers. Roblox is a flywheel getting ever faster

Every company has a flywheel. At its core, a flywheel should explain how the business works. A flywheel starts slow, but starts to whirr and get faster due to Newton’s first law of motion. Roblox’s is a attactive mix of engagement (“stickiness”), spend and content encouraged by the spend. As all theme park owners know, more time spent directly correlates to more spend -- this is a universal truth for all things from hotels to video games to restaurants to social media. Roblox is incredibly sticky -- as we mentioned +11.2 billion hours engaged in Q3 2021 alone. We see Roblox’s momentum as ever-increasing as its very compelling flywheel continues to whirr.

Introducing Salvatore Ferragamo

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund own a share of Salvatore Ferragamo (BIT:SFER), an iconic brand globally renowned for its finely crafted fashion products and accessories. Rising to fame as a shoemaker for movie stars in Hollywood such as Marilyn Monroe, Salvatore Ferragamo has grown from a small presence in Florence, Italy to become one of the most respected fashion brands in the world. Ferragamo has a strong heritage in the art of craftsmanship, with the founder leaving behind 20,000 models and 350 patents. While performance in recent times has been sluggish, we believe the appointment of former Burberry CEO, Marco Gobbetti, represents an inflection point in the revitalisation of the brand and its valuable archive.

The Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund has owned Salvatore Ferragamo since July 2021 when the stock was trading at an attractive discount to our valuation range of €25.40 to €31.57, offering potential upside of +49.65% to +86.04% from the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund’s historical cost basis as at 22 November 2021, and +27.49% to +58.49% potential upside from the current market price of €19.92 as at 22 November 2021. To learn more please read our Investment Summary Report by clicking the button below.

Why we own Visa and Mastercard

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares fund own shares in both Visa and Mastercard. Recently both businesses have, in our opinion, been priced at a discount to their intrinsic value. We thought it pertinent to talk about why we think Mastercard and Visa are some of the best businesses in the history of mankind, and why we are buying more -- if you’re being offered a chicken that lays golden eggs, you take the chicken.

Here is why we like Visa and Mastercard so much. We like very simple businesses. A simple business model often equates to superior business performance. We then think about companies which are likely to generate meaningfully more amounts of money in the next ten years than they do now. Let’s borrow Charlie Munger’s phrasing and call these the “probables”. It’s much easier to understand something that’s probable when it’s simple. Mastercard and Visa are the epitome of simplicity - they are in the ticket clipping business.

They clip the ticket on every transaction made via their vast networks -- often they clip the ticket twice, or three times -- for money to travel from a consumer to Merchant X, the money moves from the consumer’s bank to a merchant bank, possibly several times depending on the complexity of the money’s journey. Visa and Mastercard clip the ticket every time the money travels. The percentage they take is tiny - an average of .15% - but they take that .15% every time. They earn a royalty anytime someone uses their network.

This has been hugely profitable for Visa and Mastercard. Payments using cards have ballooned over the last few decades as they have become integral to everyday use -- a hundred years ago leaving the house without your cash or chequebook seemed unthinkable. Now leaving the house without your card (whether it is physical or on your phone) is unthinkable. For all intents and purposes, cards are our main form of money.

This is partially due to ease of use. Cards are portable and light and often weightless -- our card details are so often saved on our devices that we don’t need to access the physical object itself. This is also partially due to accessibility: Visa alone is accepted in 54 million locations; Mastercard’s is similar. Visa can process 24,000+ transactions per second (Bitcoin, for the crypto-enthused, processes around just 7). It is so blindingly omnipresent that it can be hard to realise what an incredible accomplishment this is. Visa and Mastercard have woven a network that encompasses the entire world

Here’s the rub: the web that Visa and Mastercard wove is complicated; it’s as if they have constructed not a moat but a labyrinth, filled with minotaurs -- Visa’s own proprietary technology, VisaNet, was first rolled out in 1973. It covers thousands of banks and millions of merchants. It’s a network which is hard to replicate, which explains why the two companies have enjoyed such a strong competitive advantage for so long -- in America, Visa commands a 49% market share and Mastercard 38%. Worldwide market share is similar, adjusted to exclude the Chinese market. American Express’ market share is only 3%.

The growth opportunity is one of simple arithmetic. More people using electronic payments means a greater transaction volume, which means Visa and Mastercard’s cut is proportionally larger. In 2010, 28% of consumer purchases were made on cards. By 2018, 48% of transactions were via card. The figure now hovers closer to the mid-50s. So here are our “probables”: it’s probable that the world’s population will increase, it’s probable that spending will increase, therefore Visa and Mastercard stand upon a stream of ever-increasing royalties, like a fly fisherman in a stream which becomes continuously surrounded by more and more fish.

In other words, the continued growth and continued economic prosperity of the world is a boon for Visa and Mastercard. It is hard to argue that our quality of life now is better than a century ago, or five hundred years ago (you might be interested to know the average life expectancy in the US in 1921 was 60 -- it’s now 80. 500 years ago it was about 35). Humanity continues to innovate and expand, and fully expect Visa and Mastercard will be there to clip the ticket.

The second opportunity is B2B (business to business) payments. Mastercard estimates that $120 trillion flows through the B2B market. Visa recently broke $1 trillion in B2B payments; their management estimates we are in no more than a “second innings” and the market opportunity is at least ten times current payment flows (ie. $10 trillion -- this still represents a small fraction of the overall B2B pie). The two companies have wasted no time in their pursuit of B2B -- in 2019, Visa launched the Visa B2B connect and Mastercard launched its own service, Mastercard Track. The value proposition they offer is similar to what they offer consumers: faster, more certain transactions paid on time. We should mention that Visa and Mastercard’s transaction fees are lower than their competitors.

A few learnings from the rise and rise of these two stalwarts, then --

i), The death of traditional cards by “fintech” disruptors has been greatly overstated. For instance, Nubank - the much lauded “new” bank with no branches and no fees which lists on the NYSE on 8 December - still uses Mastercard for their bank cards.

ii), The prestige card - American Express - has largely been a victim of its own prestige -- as per a 2017 NYTimes article - Amex, Challenged by Chase, is losing the Snob War:

But it’s an uphill battle for Amex, in part because the company is fighting an image of conspicuous consumption it has cultivated for decades. Amex sold a dream about what success looks like, a universe where handsome men and glittering women murmur about second homes over decanters filled with expensive booze.

iii), The physical quality of a card matters less and less - it is often on our phone, via NFC (near field communication chip), or used to make payments online. This explains partially why American Express’ moat has eroded so significantly in the last decade, as previously physical things have become more and more digitised.

iv), There are two big growth opportunities here: the continual shift to spending using cards, and the B2B opportunity.

v), Visa and Mastercard are the best positioned operators to take advantage of rising consumer spending and a growing population. To borrow for Munger again, they are “probables”.

Introducing Refining NZ (Channel Infrastructure NZ)

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund own a share of Refining NZ (NZX:NZR), New Zealand’s only oil refinery since 1956. On 8 August 2021, shareholders voted overwhelmingly at a special meeting to approve the transition to an import terminal and rebrand as Channel Infrastructure NZ. This ‘pivot’ is forecast to generate significantly more stable earnings compared with the inherent volatility of oil refining, deliver superior “through the cycle” returns to shareholders, and position the company to meaningfully participate in the decarbonisation of the New Zealand energy market.

The Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund has owned Channel Infrastructure from April 2020 to present delivering a net return of +49.12% to date. Channel Infrastructure trades at an attractive discount to our comparable companies valuation range of NZ$1.19 to NZ$1.43, offering a potential upside of +108.67% to +152.24% from the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund’s historical cost basis as at 16 November 2021, and a +36.24% to +64.68% upside from the 16 November 2021 market price of NZ$0.87. To read our Investment Summary Report please click the button below.

On How We Invest

It is never far from our mind that the shares we own have a company at the other end of them. This seems obvious, yet in our experience the most important things in investing are the most obvious (“Rule #1: Don’t lose money; rule #2: Don’t forget rule one.”). Yet it bears repeating -- every single one of the companies in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund portfolio are businesses with employees, premises, lunch breaks, janitors and everything else. We, on behalf of our investors, own a fractional interest in these companies. This perhaps escapes the mind of those who trade stocks faster than the speed of light; call us old fashioned -- but we like to own a portion of a company and let it do what it does best.

To paraphrase that great prophet, Warren Buffett, it wouldn’t matter to us if we didn’t have quotes from the stock market for days or months at a time -- for Spotify or Disney or any of the other companies we own shares in. We’re quite certain Disney is going to keep creating top quality entertainment and experiences, and that Spotify is going to be providing you with the music and podcasts you love, and your kids will be entertained by Roblox (we, too, entered the metaverse this year -- if you haven’t played Roblox, you’re missing out). It’s no different to owning shares in a privately owned business: we don’t need confirmation every day that people are still using Mastercard or Visa (two other Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund holdings). We feel incredibly confident that Visa and Mastercard will continue to be used for years to come. We sleep well, we hope our investors do too.

This is the long and short of how we select companies. It’s no different to if we owned the whole company (we would certainly love to own the whole of any of the companies the Fund holds shares in, but alas, we’re not as big as Berkshire Hathaway yet). If the company is well-run and has a substantial competitive advantage then the best indicator of its value is its annual and quarterly earnings, and further to that, its multi-year record. However, the stock market provides a wonderful mechanism for taking advantage of the mispricing that sometimes occurs. This is where we, your investment managers, come in. The more mispriced a stock is the more we like it -- it’s like the proverbial old lady who finds a previously unknown Van Gogh in her attic. The beauty of the stock market is that often those Van Goghs are right in front of you.

Quarterly earnings are a reasonable indicator of where a company is headed. On Wall Street they call this “earnings season” (think of it like duck hunting season, except this happy event happens four times a year). Well -- this earning’s season was a doozy. In the finance sector alone, total earnings were up an average of ~42%! Companies we own shares in also reported whopper earnings. Roblox’s quarterly “bookings” (its metric for revenue) was up +28% year on year, whereas Avid Technology’s subscription growth was up +56.4% YoY. Spotify’s number of subscribers was up +19% YoY -- 172 million people now pay Spotify a monthly fee for the pleasure of a virtually limitless audio library.

These earnings confirm our continued faith in these companies and their world-beating businesses; they also, we think, protect against the real costs of inflation -- recently US inflation was pegged at 6%, a level not seen since the early 1990s. The joy of owning businesses like Spotify is that they effortlessly incorporate inflation; their prices simply go up. The best sort of businesses to own in times of inflation are ones that factor in the change in price simply by default. In that regard, Visa and Mastercard are perhaps perfect inflationary businesses. Their business is, quite literally, taking a very small portion of the billions of transactions that occur per year. It wouldn’t matter to Visa and Mastercard if we suddenly started using salt as a currency, as it once was: they’d surely figure out a way to take a margin from it.

We also like companies which are predictable. There’s a lot to be said for Twinings English Breakfast Tea (a favourite here at the office): it isn’t spectacularly different and there are many more teas out there, but it is consistently predictable. The companies we own a fractional interest in are as steadfast as English Breakfast Tea -- Visa will continue to fuel payments the world over, Richemont will continue to make the world’s most beautiful and exquisite jewellery (if you are looking for a present for a loved one this year, look no further than Cartier) and Madison Square Garden (a recent addition) will continue to be the premiere entertainment venue provider in New York. The world has undergone some major changes in the last ten years (that ancient Chinese curse comes to mind -- “may you live in interesting times”) -- yet the basis of how we invest is unchanged. We’re still drinking copious amounts of tea, and we’re still investing in some of the best companies in the world

Introducing Avid Technology

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares fund own shares in Avid Technology, an industry-leading provider of high-end video and music production software. Avid Media Composer is the dominant film editing software amongst Hollywood and multi-million dollar productions, while ProTools, the audio editing equivalent, is the dominant software in the music industry. Like Adobe before it, Avid is transitioning its business model to SaaS (Software as a Service). To learn more about Avid Technology, please read our investment summary report by clicking the button below.

All Songs Considered*

One of the great investment stories in the last couple of years has been the reemergence of the music industry. Universal Music Group (UMG) spun-off from Vivendi earlier this year, Warner Music listed last year; and the the catalogues of musicians are being snapped up at record prices -- UMG paid US$300 million for Bob Dylan’s catalogue and funds like Hipgnosis Songs Fund have quickly snapped up catalogues as diverse as those of Blondie, Neil Young and Fleetwood Mac.

The graph below from the Financial Times demonstrates the success of this investment story:

Source: Financial Times 27 October 2021

There are a couple of interesting features of the graph. The first is the dip -- this is due to the music industry scrambling to reorganise after two distinct disruptions -- 1), Downloaded music (iTunes, Napster, etc), and, 2) Streaming music (Spotify, Apple Music, Youtube Music, etc).

We are cautious when it comes to calling something a “disruption”. Buzzwords are easy. However, these two events were real disruptions which caused a sector-wide decline. Now the framework for a streaming-first industry has been defined and industry revenues have corrected themselves; they are on the ascent. It is a remarkable recovery and a testament to how an industry can reorganise around a disruption.

The second thing of note in the graph is the increase in performance rights. These are rights stemming from using the song live or in content. This reflects the success of TikTok and short-form content, where a “meme song” is integral to the content itself. The beauty of TikTok’s format is that its approach to songs is ahistorical: a Fleetwood Mac song (Dreams) can become popular with an audience who have never been familiar with Fleetwood Mac in its original incarnation (or even knows who they are); likewise a completely unknown song can shoot to stardom -- like NZ’s own Benee’s Supalonely. Every time a song is used on TikTok for a seconds-long dance or meme a performance royalty is paid. This is a democratisation of song rights, which previously were via cashed-up studios.

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund have exposure to the music industry’s resurgence in three ways: via Spotify, Universal Music Group (UMG) and Tencent. Our to-date return on our Spotify holding is approximately +130%, from inception at 12 November 2018 (a 34.19% IRR). We continue to see opportunity in the company; their latest quarterly results are encouraging -- podcasts and better targeting drove advertisement revenue up +75% YoY, while a price increase (reflecting Spotify’s pricing power) increased premium subscriber margins to +29.1%.

We like Spotify because it commands a royalty on the listening habits of its ~381 million users (Spotify estimates this will grow to ~400 million by the end of 2021). We think this is analogous to Charlie Munger’s famous valuation of Coca Cola, where he said Coca Cola takes a royalty on “sips”.

Spotify meaningfully differentiates itself by its significant investment in original content (the Joe Rogan podcast is the most well-known example, recent acquisitions include Call Her Daddy and Dax Sheppard’s Armchair Expert). The effect of original content is that it renders Spotify a one-stop shop for users: they can log on, listen to Joe Rogan and cue up a playlist afterwards (an often overlooked strength of any platform when it achieves scale; once you’re hooked in -- with all your playlists, preferences, and an algorithm that knows your trade -- changing to a competitor is not a light undertaking).

Yet we are also interested in Spotify’s recent acquisition of Megaphone, an advertising technology company and Anchor -- a podcast creation tool. We think this may point to Spotify’s growing ambition: to not just be a content platform and creator, but to empower other creators. We think this sentence from Lucas Shaw’s recent Bloomberg column to be clarifying:

“[Spotify CEO Daniel] Ek has started to talk about radio the same way Netflix talks about cable TV. More people still listen to radio than stream audio, and more advertising dollars are spent on radio than on streaming. Yet while radio has flatlined (like TV), streaming is getting all the new money.”

We consider the +75% YoY growth in ad-supported revenue to be a sign of Spotify’s strategy paying off. Spotify’s ambition is audio, whole.

Investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund also own shares in UMG and Tencent. We received shares in UMG via a spinoff from our investment in the French holding company Vivendi. UMG is the world’s biggest record label and a beneficiary of the music streaming story -- its recent quarterly results demonstrate its strength; streaming revenue is up +16.1% YoY and music publishing revenue is up 19.8% YoY. This provides exposure to both sides of the transaction: the creation and publishing of the music itself (UMG) as well as the streaming and consumption of it (Spotify).

The third way investors in the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund gain access to the music story is Tencent. Tencent is a Chinese conglomerate with broad interests - from fintech to gaming to social media to music. Tencent owns 10% of UMG, 9% of Spotify and 5.2% of Warner Music.

We like to have our cake and eat it too when we can. Here we see a rare opportunity where we can do just that -- on one side, secular headwinds mean that record labels will have sustained levels of revenue from both increased streams and performance rights. On the other hand, increased streams mean streaming platforms like Spotify take a royalty on each stream (whilst Spotify’s foray into the content field means it clips the ticket twice -- on content and streams.

Whichever way you put it -- it’s all cake.

As of 3 November 2021, The Elevation Capital Global Shares fund owns shares in: Spotify (SPOT), Universal Music Group (UMG) and Tencent (0700 HK).

*All Songs Considered is a NPR radio show, home of the Tiny Desk Concert series.

Why we find SaaS compelling

One of the themes we have become increasingly interested in is SaaS (Software as a Service). The old model of software was predicated on selling it once, like any other product you might buy -- a fishing rod, a cup or a new set of dinnerware. Companies would spend years developing a new piece of software, spending millions in the process, and then eventually sell & market it which would provide a large influx of cash. It was a cyclical business: a new version of Photoshop might generate a lot of revenue for Adobe but the years spent developing the next version would be fairly lean. This is not remarkable. It is how most consumables work. The unique thing with software is that once it has been produced the cost of production becomes almost zero. A car company still requires the raw materials to manufacture a new car. A software company essentially just needs to copy and paste the software itself: it is infinitely replicable with very little material cost.

So, then, the idea of selling software as a one-off makes little sense when you consider there is no inherent cost of reproduction. There is no iron or rubber or glass. Yet this served as the dominant software model for many years. This was largely due to the high cost of storage, relatively slower internet speeds and the lack of “the cloud”. The cloud, in many ways, made SaaS possible -- the cloud takes advantage of cheap, mass storage solutions and fast internet, as well as similar peer-to-peer architecture. Once the cloud made SaaS feasible, companies with forward-thinking management quickly shifted to the model -- the paramount example is probably Adobe, who transitioned in 2012 to a fully SaaS model: users would pay monthly for access to some, or all, of Adobe’s creative suite. The fee would be nominal -- $50 for the full suite rather than hundreds of dollars for the one-off product. It was like having a subscription to Netflix or the gym -- small recurring nominal fees rather than a large one-off fee.

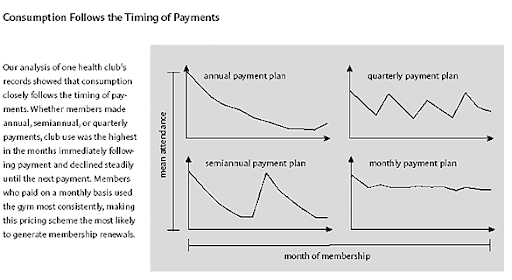

Rationally small incremental payments should be treated the same as one large payment. A SaaS subscription of $50 per month for a year is precisely the same as a one-off fee of $600 per year. This doesn’t consider mental accounting -- mentally we treat $50 a lot differently to $600. “Big ticket” purchases occupy a different part of our brain compared to a “nominal” amount. Soman and Gourville presciently wrote as much in 2002 in the Harvard Business Review:

Consider this example. Two friends, Mary and Bill, join the local health club and commit to one-year memberships. Bill decides on an annual payment plan—$600 at the time he signs up. Mary decides on a monthly payment plan—$50 a month. Who is more likely to work out on a regular basis? And who is more likely to renew the membership the following year?

Almost any theory of rational choice would say they are equally likely. After all, they’re paying the same amount for the same benefits. But our research shows that Mary is much more likely to exercise at the club than her friend. Bill will feel the need to get his money’s worth early in his membership, but that drive will lessen as the pain of his $600 payment fades into the past. Mary, on the other hand, will be steadily reminded of the cost of her membership because she makes payments every month. She will feel the need to get her money’s worth throughout the year and will work out more regularly. Those regular workouts will lead to an extremely important result from the health club’s point of view: Mary will be far more likely to renew her membership when the year is over.

Source: Harvard Business Review

We think this captures the unique power of SaaS. Behind every good business is a strong psychological rationale. There is a number of practical reasons why SaaS works, as well -- infrastructure and software can be updated rapidly, rather than a two-year development cycle; the product is always the newest possible product.

We have acted accordingly and added SaaS-based companies we consider to offer compelling value. We recently added both Squarespace and Avid Technology to the Elevation Global Shares Fund. Squarespace is the market leader in website hosting & design service: it has a growing base of subscribers and effortless integration of commerce and scheduling services. Squarespace has +3.9 million subscribers who pay an average of $193 per subscription. This, we think, is a succinct illustration of the power of SaaS economics (we use Squarespace ourselves, for this very website).

Avid Technology (Avid) is the leader in software for “big budget” film and music editing. Four in five Hollywood productions are made using Avid’s Media Composer software. The majority of major label music releases are made with ProTools, their music editing offering. The amount of investment being made in both fields of high budget content by Disney, Netflix, Amazon, Discovery and so on necessitates more use of Avid’s industry-essential software. Avid was hesitant to move to SaaS at first; new management has spurred the move to SaaS since 2017 and the results look incredibly promising. Look out for our forthcoming research on Avid and Squarespace.

September 2021 Global Shares Fund Results

Realisations in September 2021

As volatility increased during September we took the opportunity to increase our cash balance and opportunistically realise several of our investments:

The Trials of Direct-to-Consumer. Or, why we own Essilor Luxottica and not Warby Parker.

Warby Parker, the direct-to-consumer (D2C) optical frame maker, recently listed on the NYSE at a valuation of +5 billion USD. The company’s frames are ubiquitous amongst a certain millennial milieu; even New York icon Fran Lebowitz collaborated with them on a version of her signature frames. Warby Parker, we think, is emblematic of the recent trend for direct to consumer (D2C) products. There’s Casper for mattresses, Great Jones for cookware in soothing shades pastel pink; Glossier for skincare; Harry’s for shaving, Dollar Shave Club for shaving, Ecosa for mattresses, Our Place for cookware, Equal Parts for cookware, Material for Cookware, Emma for mattresses, Winkl for mattresses, Bailey Nelson for optical frames -- is the pattern clear, yet?

Millennial-focused D2C companies tend to share a few characteristics. The New Yorker touches on the first in its piece on Great Jones[1], a cookware company.

A strange but increasingly familiar kind of illusion underlies the D.T.C. (D2C) model. What Great Jones sells has less to do with the functionality or provenance of its kitchenware than with fostering the customer’s sense of in-crowd belonging online. As Albert Burneko put it in Defector, the brand is for “people shopping for cookware that will make them feel like they are pals with Alison Roman”.

The first element, then, of the D2C model has nothing to do with the product and everything to do with the ‘thing’ the product implies. The second element is the aesthetic. The millennial product aesthetic is almost always “well” designed, has soft edges, soothing tones and a nod towards minimalism. Molly Fisher wrote that “[the] design is soft in its colors and in its lines, curved and unthreatening” in her piece in 2020. The second element is aesthetic. Warby Parker has this in spades, its hipster aesthetic is a sanitised version of the old hipster aesthetic of Vice-magazine c.2007. The third aspect of D2C is the actual selling of the product. It sells directly to the consumer. This may seem like stating the obvious -- yet that is the model. It is not particularly different to Avon selling products door-to-door in the 1970s; the internet is the salesman.

The model has issues. Generally D2C products have razor-thin margins because of the number of competitors. Casper, for instance, is competing against all the other D2C mattress manufacturers and traditional manufacturers. The competition reduces margins and often the products are affordable -- this is the promise of the millennial D2C company. The affordable products mean they need to sell a lot of mattresses, or a lot of glasses, or a lot of pots & pans. Yet the biggest issue is the overwhelming similarity of the product offerings: local D2C firm Bailey Nelson makes frames that are more or less the same as Warby Parker’s own offerings.

The D2C conundrum is acquiring new customers, quickly. If you are a company landing high-value contracts like another Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund holding, Palantir, then producing a bespoke model and wooing one client with charm and acumen for months is reasonable. A Palantir contract is often worth hundreds of millions. If you consider that a D2C business pitches a “contract” to a consumer (in the case of glasses or a mattress, we would argue that decision is a long-term decision in spite of the low cost of either) then it isn’t logical to spend months wooing a customer on a $100 pair of glasses. So a D2C must win a “contract” with little spend and fast, because volume is important in a low-margin business. How does a D2C with marked competition and little-to-no differentiation win the “contract”?

In other words, Warby Parker is up against a lot. It trades around 15x revenue, a princely sum to pay for a company with no key differentiator. The Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund owns shares in Essilor Luxottica, which trades at ~5x revenue, which is a far more reasonable price to pay for a company which has a virtual monopoly on the global optical industry.

Essilor Luxottica is the anti-Warby Parker. Warby Parker has no competitive advantage. Essilor Luxottica has the advantage of scale, and the advantage of a virtual global monopoly. It is really the vision of one titanic man who is referred to solely as “il Presidente” in the optical industry -- Leonardo Del Vecchio. Del Vecchio turned Luxottica into a global behemoth -- chances are, you’ve purchased glasses from them. Del Vecchio pioneered the idea of licensing fashion brands for frames and then expanded his reach to retail -- Sunglass Hut, OPSM and Oakley. In October 2018, Luxottica merged with the biggest lens maker in the world, Essilor. Del Vecchio in effect took control of the entire supply chain -- from manufacturing frames & lenses to the distribution of them and the sales of them. The entire model is vertically integrated. Essilor Luxottica also owns a number of D2C brands (Clearly, Smartbuyglasses, etc) which significantly undercut Warby Parker itself.

This is why the Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund owns shares in Essilor Luxottica and why we did not invest in Warby Parker. Essilor Luxottica’s pricing power extends from manufacturer-to-consumer across multiple retail chains and brands. Essilor Luxottica offers the illusion of choice yet ultimately it owns it all. Warby Parker offers a low-cost, undifferentiated product against a sea of competitors.

Elevation Capital’s earlier reports on Luxottica (pre-merger with Essilor) can be found below:

Elevation Capital - Luxottica Report - December 2016

Elevation Capital - Luxottica Presentation - December 2016

Manual of Ideas - Why Luxottica Remains an Attractive Long-Term Opportunity

[1] https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/great-jones-cookware-and-the-illusion-of-the-millennial-aesthetic

You work hard for your money. We make sure it works harder.

The last thing you want when you’re putting in the hard yards at work is your money just cruising along for the ride.

At Elevation Capital, we make sure your money stays on task and works every hour of every day. Kind of like boot camp for cash.

Elevation Capital is a local firm respected and awarded for their commitment to independent thinking and disciplined investing. They closely manage their clients’ money through their proprietary tool; the Global Shares Fund.

From here it gets sent off to work in worldfamous companies like Disney, Spotify, Heineken, Estée Lauder, Fever-Tree, Swatch, Palantir and many others.

The Elevation Capital Global Shares Fund has a long track record and has delivered net returns of +11.66% per annum over the last 5 years* for its investors.

You don’t even need a huge lump sum to get involved. For an initial investment of just $100 and as little as $25 a month, you can get your money working harder than you. When you get a minute, let us show you how.

To apply online or find out more information, visit: globalsharesfund.co.nz

Just another example of independent thinking and disciplined investing from Elevation Capital.

Elevation Capital Management Limited is the issuer under this offer. A Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) is available at: www.globalsharesfund.co.nz